|

Experiencing the Humanities

A Web Textbook

|

|

|

Experiencing the Humanities

A Web Textbook

|

|

14. Literature: The Language Art

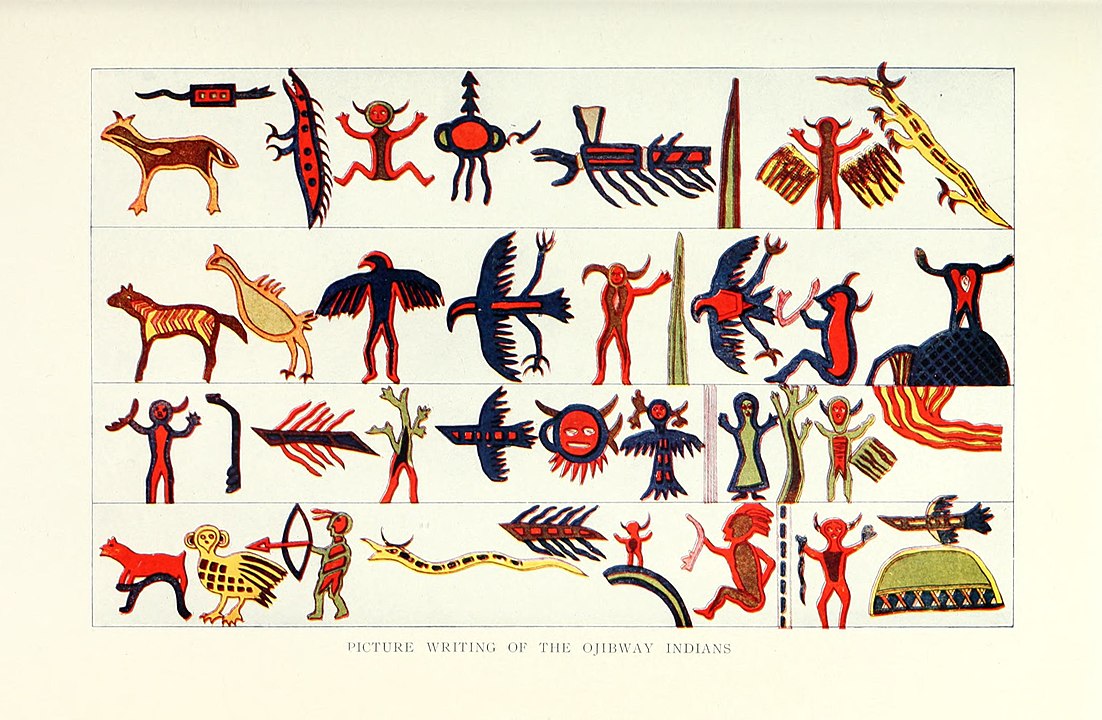

Above: A story told in “Picture Writing of the Ojibway Indians”*

Chapter Fourteen of

by Richard Jewell

Introduction--Art That Can Be Read

Are the above pictures part of literature? Literature is written art--art in which a writing device is used to put words on paper, whether as images or the more common alphabet. Throughout tens of thousands of years--as humans have slowly moved out of their caves and trees and into self-built dwellings around campfires--these humans have told stories, real and made up. Whether the stories were about the latest hunt for a bear, a great war, or a great love story, they were told orally and sometimes performed.

It is only in the past five thousand years that people began writing them down. stories have been told. In about 3000 BCE, humans began writing down their statistics about their harvests--and their stories, songs, and poems. Some of this writing was in "pictographic" form, such as ancient Egyptian hieroglyphs, Babylonian cunieform, and the North American Ojibway Indian pictographs above. Much of it was--and is even more so today--in "alphabetic" form: sentences using the letters of an alphabet.

In whatever way humans began writing, they liked telling stories. People always have gathered around the campfire, the indoor hearth fire, the radio, and now the digital screen to hear and watch others give them a great story, songs, or poetry. Great literature--the best of such writings and tellings--have strong and important visual images (as in the pictures above), sounds (talking and more), and other sensory details (such as smells, tastes, and touches). The best stories, poems, and songs--the best literature--use all five senses, fascinating characters, and strong, interesting events organized into a theme or a plot.

But just what is literature in all the writing that exists? Here are some basic types of what is called "literature":

fiction

stage play

poetry/song

literary essay

creative nonfiction

screenplay

comic strip script

video script

comic book script

Though all forms of literature are written, some of them are meant for performance as are plays and video scripts, and some are mixed with visual forms to become comic books, cards, or posters.

Some forms of writing are, primarily, a performing art or an art work that is more visual than written. Plays for stage, film, and other digital shows are obvious examples. However, such works also may be highly respected works of written literature, too: art that can be both written and performed, made of letters and made of moving visual images.

In addition, while some literature may seem meant to be read quietly, on your own, much of it is meant to be read out loud. Poetry and plays are examples. Poetry and plays often come fully alive only when you read them out loud, even if you do so alone, on your own. To fully appreciate poetry and plays, someone--you or others--should perform them. Plays and other performance arts are discussed in "Chapter 11."

However, even though you may read some types literature alone--such as novels, creative nonfiction, and poetry--usually you will be reading it using your "inner voice," the silent voice in your head. So even these forms of literature usually are, for most of us, "performed by voice" as human beings have done for thousands of years, making all literature a type of oral, or voice, expression. In essence, this means that when we read literature, we are to a great extent talking to ourselves, even if it is in our heads, even if it is an inner whisper. Literature thus is very much both a written form and an oral form.

But more is needed than talking to ourselves or someone else for writing to be truly "literature." Literature actually may be defined as any writing that has--in some way--artistic beauty.

A grocery list (unless, possibly, done as part of a longer literary work) is not literature. War and Peace by Tolstoy is. So are Peter Rabbit by Beatrix Potter, significant parts of great religious works of art such as the Judeo-Christian Bible or the Hindu Bhagavid Gita, Shakespeare's plays and poetry, and finely crafted nonfiction such as Plato's Republic or Martin Luther King's "I Have A Dream" speech.

Sometimes it is not so much the subject matter that makes a piece of writing literature, as it is the way in which the subject matter is handled. The grocery list mentioned above could appear in a beautifully crafted humorous article or fiction story, in a finely tuned poem, or even in a speech, thus giving even its simple grocery-list contents a special beauty or meaning. Sometimes the subject matter does make a difference, though: important subjects sometimes lead people to talk and write more eloquently.

When people write or speak of such subjects as visions of the soul, the eternal conflict between good and evil, great romance, or the tragedy of loving or of warring, the subject matter itself may incline them to create written works of art that can move everyone else deeply, even change people's lives.

A very brief history of literature highlights the following events. Even though writing by humans began around 3000 BCE, before 500 BCE there was very little real literature. The few pieces of literature that did exist throughout the world mostly were on clay tablets or carved in stone--clay and stone were the first mediums of the writing arts. Most literature was still oral in those days: part of an important oral tradition in most countries and continents. In fact, storytelling was a profession in more civilized ancient countries, and storytellers would make their living by memorizing great classics of myth, legend, and truth from each other, then repeating them to enraptured audiences.

Papyrus, rough paper-like material made from reeds, came into more common use after the fifth century B.C. in Europe and Africa, and similar materials came into use about the same time in the Far East. The mediums of papyrus, paints, and inks made writing easier.

Some of the earliest classics of written literature began to appear from that period of history, works such as the Old Testament of the Hebrew Bible, the works of early Greek philosophers and playwrights, the Tao Te Ching of Lao-tzu, the Vedas and Upanishads of India, and other great works of art. From this rough papyrus or "paper," more refined and mass produced versions were developed as the centuries progressed to medieval times. Early through late medieval times saw monasteries (in the Western world), universities (in the Islamic cultures of North Africa and the Middle East), and the courts of kings and princes (in the Far East) collecting older writings from wherever they could, gathering them into small libraries, and copying them by hand to share with others. In 1408, for example, the Yongle Dadian--a copy of all existing writings in China, was made by order of Chinese Emperor Yongle. It is through the sometimes heroic but more often tedious work by a limited number of intelligent copiers that many early written works have been preserved, even while many others--great works of literature, religious scriptures, and histories--have been forever lost.

However, even with copying by hand, reading and writing literature still were activities few engaged in. Many works of art from oral traditions were written down such as myths, popular events and plays, common songs, speeches commissioned to be written by kings, and the like. But in any given century, the choices of "new works" to read were few.

Many people associate the word "literature" with novels (made up books) and fictional (made up) short stories. Curiously enough, telling made-up stories in written story form is a mostly recent art. The novel and the short story, as such, did not really exist until after moveable type was invented in medieval times by Gutenberg, and after the slow spread of general education in reading and writing that followed the invention of moveable type.

However, with the spread of reading and writing, suddenly large numbers of people had the ability and opportunity to sit down with a book of their own and actually understand what the words in it were saying. Literature exploded, both in quantity and variety.

Now there are have thousands of great works of literature to choose from, and hundreds of thousands of quality minor works of literature available to readers, with more being produced every day. In addition, literature in the present time is going visual: the predominant way of getting a finely crafted story is now, for most Americans, the television screen. Just as books used to be for the privileged few, so was viewing plays. Now not only have books become common personal items, but so has the viewing of plays. The TV screen brings into each person's own hands the means to see any great literary work in visual form which he or she may wish to.

Most forms of literature tell, in some way or another, stories. Stories can be true or made up, stories are in songs and in plays, they may be found in simple poems and in complex speeches, and they exist in novels and short fiction.

There are stories like Ulysses and the Sirens who sang so beautifully they tempted men to crash upon the rocks in seeking them, stories that make people sit on the edges of their seats. There are stories like those of Aristophanes or Woody Allen that keeps audiences laughing throughout them. There are stories like Shakespeare's Romeo and Juliet that make people cry, even stories like those of Moses, Krishna, or Confucius that shape the ways hundreds of millions of people throughout the world live and believe.

Perhaps the easiest way to understand how both content and style form a beautiful, moving story is to look at the basic plan or structure of storytelling.

That structure often may be summarized as follows:

plot--events with a purpose

character--people talking and acting

description--surroundings and symbols

"Plot" is the basic plan of a story. It is the person, problem, and solution-- the hero/heroine, obstacles, and outcome. It is the "Once upon a time X had a problem with Y" sentence often found in some form or way in the first page of a story. It is also the series of events that the good characters go through--or take upon themselves--to try to get to a happy ending.

"Character" is the characterization or development of the people in a story. Character means that the reader gets to see characters talking, thinking, feeling, and acting. They experience difficult times and pleasant times. Their talking and acting demonstrates their hopes, dreams, inner and outer selves, needs, and pasts.

"Description" means well described settings, sensory details about the characters and their actions, and, often, good simile, metaphor, and other use of symbols to help us see what people and things in the story symbolize or stand for.

Let's look at each of these three elements of stories in turn.

Plot--The Plan of the Story

"Plot" is the basic structure, skeleton, or direction of a story. It is who did what to whom, when, and why. The difference between just an event and a plot is that an event is, simply, a description of something that has happened. But a plot is a description of how a person goes through change.

This change, this pattern, has been described in a number of ways. Here are some:

| person

hero/heroine(s) |

problem

villain(s) |

solution

goal |

Someone or some group of people that are basically good or

trustworthy have to be at the center of the story, they must have problems of some kind, and

they must try to reach a goal or end to their

problems, or create a successful change. They don't always win--some of the best

tragedies show people losing--but they must try with all their heart.

It may help to imagine the plot of a story as a character battling to climb over

a mountain of trouble in his or her way:

Obstacle Mountain

Gabriel R. Jewell, Obstacle Mountain.

Used by permission.

Copyright 2019, all rights reserved (also in Chapter 11).

The "rising action" is the events leading to reaching the goal (or forever failing to reach the goal). The "falling action" is the end of the story--what happens after the denouement, as a result of it. Stories usually are composed mostly--perhaps 90-99%--of rising action. The falling action or denouement is simply there to provide what Aristotle in his famous booklet "Poetics"--a description of how tragedy and comedy are written--describes as relief and happiness (or tears of grief), which is the audience's final release of emotion at the end. Some modern stories even do entirely without a denouement: they simply end right at the moment the goal is achieved.

This is how a plot is organized. But it must also have well developed characters and good descriptions to make it enjoyable and meaningful to read.

Character--Unusual People or Unusual Lives

"Character" means the development of people in a story who are:

1. identifiable

2. interesting

"Identifiable" means that a reader can either identify with the characters because they seem like him or her, or the reader has experienced other people like them. In short, the characters must be believable in an immediate and personal way.

Romeo and Juliet from Shakespeare are, for example, very identifiable, very believable: at some age or time in one's life, many people can identify with one of the two lovers, and most people have watched others who act like Romeo and Juliet.

Usually a story people enjoy will have at least one main character--a hero or heroine--whom the readers can directly identify with: someone who makes others say, "That person is like me," or "I can imagine myself being in that person's shoes."

"Interesting" means that the characters must not only be identifiable-- believable--but also more interesting than the normal run of people in life. Either the characters must be unusual people, or they must be normal people living unusual lives. They must also be attractive in a certain way. Their attractiveness must be "normal" in important ways, but usually there is a slight flaw--physically, psychologically, or both--that makes the character a little different in an even more interesting way.

Some famous unusual characters in literary history are the great figures of any major religion (remember that true stories can be written as good literature, too); mythic figures such as Thor, Venus, and Coyote; and book heroes, heroines, and villains such as Tom Jones, Heidi, Darth Vadar, Nancy Drew, and Harry Potter. However, even when unusual people are heroes, heroines, or villains in literature, much of their appeal is how much they are, in some basic ways, like ourselves or people we know. This appeal to readers' own personalities or the personalities of people near them usually is the central attraction of a good character.

The same attraction exists for the other kind of literary character: a normal person living an unusual life. There are many examples of such characters--in fact, much of the best literature may be about characters with whom most readers can closely identify. Tiny Tim and his family in A Christmas Carol are one example; so is Anne Frank or Agatha Christie's bumbling but loveable and intelligent detective, Poirot. These all are characters with whom large numbers of readers can identify because the characters are so much like average readers that readers can put themselves in the characters' shoes and ask themselves, "How would I respond to what this character must go through?"

In fact, it is said that there is at least one good book lying within each person--if he or she only knew how to write it. If this is true, it is because all of us experience the deep joys and beauties of life, and great sorrows and losses, too. It is readers' own experiences that help them identify with normal characters in literature who are going through unusually good and/or bad times. We imagine ourselves in their shoes, and we imagine ourselves acting like they would in trying, difficult times.

Authors of good literature are very concerned to develop good characters. Sometimes their characters just leap from their brains, nearly completely formed. At other times, characters must be developed step by step to make them three- dimensional--to make them have the fullness and believability of human life. Believable characters usually have some of the following traits developed on the pages of their stories:

how they look

how they sound

what they wear

their emotions, desires, beliefs

where their work

their hobbies

their dark secrets

their past

future hopes, goals, and plans

their family, friends, and relationships

Even if such traits are sometimes only briefly hinted at, it is the variety and depth of these that help make a character three-dimensional. When combined with a plot that makes them strive with their soul to change and be better, three- dimensional characters easily will move readers to tears of joy, laugher, and sorrow-- if they also are well described.

Description--Sensory Details and Symbols

"Description" is the words used to describe the characters and settings--what people and things look like, sound like, and feel like. There are a number of techniques authors use to develop good descriptions. Some of the most important are as follows:

the 5 W's of journalism

the 5 senses

active verbs

use of symbols

The "five W's" of journalism are

WHO

WHAT

WHERE

WHEN

WHY (or HOW)

The traditional news article--and many good stories--tell readers in the first several sentences who and what the story is about, where and when it is happening, and why or how it is happening. These are natural questions to ask, and good stories usually describe--or at least hint at--what the story is about in the very beginning.

The beginning of a story makes a promise of sorts, displaying the type of people, the setting, and the style or mood that can be expected for the rest of the story. Readers continue to read the story only on the basis that the author will, in effect, keep this promise. The 5 W's of journalism are one common way of supplying this promise.

The "five senses" are

SIGHT

SOUND

TOUCH

SMELL

TASTE

One of the most important differences between a good story and a bad one are the details. Good details may be many things, but in stories, often, they are sensory details. The use of the five senses helps a story frequently tell about just one person or group of people in one place at one time. In addition, a story feels much more three-dimensional, more sensually whole to readers, when all five senses and not just one or two have been used.

"Active verbs" mean simply that authors often try to make movies, not just paint pictures, when they are creating scenes. In other words, authors use active verbs to show people and places in action-- moving, breathing, and living --rather than frozen in time.

Not all authors use this technique, but certainly most of the ones who are successful at creating best-selling literature do this. Active verbs means that instead of describing a dove, for example, sitting on oak tree, it often is better to show the dove flying down to the oak tree as the tree branch waves in the wind. This method creates a spare but intense style of descriptive writing as often is seen in good journalistic news writing or, for example, in the Chinese-style writing of some of Pearl Buck's novels.

"Use of symbols" is another important part of descriptive writing. Symbols are individual things, acts, or people that stand for other ideas, events, or people. For example, in the literature of many cultures, fire stands for anger or cleansing; or, for example, a parade or circus stands for how it feels to live life. Sometimes symbols are used just briefly in passing, as in a sentence like "She ran as fast as the wind." At other times, a whole story symbolizes something great or important, such as romantic love and sacrifice in Romeo and Juliet.

The simplest formula authors often use for symbolism is the "like a" formula: something is "like" something else. The most complex or richest form of symbol occurs when a whole story rises to special heights of meaning because it speaks to thousands or even millions of people about something basic in the human condition. This is, in fact true of all great art--it is symbolic of readers' own lives, and so it rises to a special level where it describes readers' own existences.

These four elements of description--the 5 W's, the 5 senses, active verbs, and symbol--are just some of the techniques authors use to deliver vivid words and worlds so that readers feel they are present in the lives, minute by minute, of the characters.

Creative Nonfiction

Many pieces of creative writing are excellent literature but do not tell a story. Stirring speeches such as Martin Luther King's "I Have A Dream" speech, or philosophical or religious writings such as Lao-tsu's Tao Te Ching, are rich pieces of literature that do not tell a story.

However, they use other elements of good storytelling, often especially the descriptive devices of active verbs and symbolism (see the section on "Description" earlier in this chapter) and any or all of the poetic devices (see the section on "Poetry" later in this chapter.)

However, there is one element that non-story literature emphasizes more than other forms of literature, and that is its organizational structure. A non-story piece of literature usually is some kind of essay: either argumentative (trying to make a point) or explanatory (simply sharing facts).

Either way, such a writing has a central post or pillar, a central theme, to it--something that can be summed up in just a sentence or two and is the very core of what the author is trying to express.

One method of imagining this central organizing theme is to think of it as the hub or axle of a wheel, and to think of the descriptive or poetic devices as the spokes that help keep the outer wheel of the writing spinning. Another method is to think of a central theme as a real post or pillar--or even, perhaps, a stick person whose clothing is the drapery of descriptive and poetic devices in which the essay is dressed.

Another method of describing this pattern of organization in most literary essays is as follows:

| Introduction-- suggests the theme | |

| Topic 1 Topic 2 Topic 3, etc. |

A series of one or many topic sections that develop the theme |

| Conclusion-- summarizes the theme | |

This form of organization often is found, partly or completely, in many stories and poems as well.

Poetry--Where Each Word Counts

Poetry is the music of the literary world. Most of its functions are performed to some extent by the other literary arts; but rarely are they performed so purely as in the seemingly simple but rich form of poetry. Some of the elements of poetry are as follows:

rhythm

rhyme

brevity

tightness

poignancy

The "rhythm" and "rhyme" of a traditional poem are obvious. Rhythm means that it has a regular beat to it, as does a song, and rhyme means that the words at the ends of some or all lines end in similar sounds. Here is an example broken into rhythm and rhyme patterns (rhythms are represented by capital versus small letters; rhymes are represented by underlining):

| We wore the hat That held the cat. |

we WORE the HAT that HELD the CAT |

In a modern poem, rhythms and rhymes are not obvious. They are still there, however. The author uses rhythm by creating the natural rhythms of speech while still emphasizing important words. And the author uses rhyme by having sounds within words and within lines rhyme with each other:

| The sun dripped sweat in tears from my brow. |

the SUN dripped SWEAT in TEARS from my BROW. |

"Brevity" and "tightness" both mean that a poem must be concise. It usually is brief, expressing a single feeling or idea in one printed page or less (though much longer poems sometimes are possible). And poems also are supposed to be tight--to be edited carefully and tightly. This means that every word must be absolutely necessary, and no extra words should be used to express the idea or feeling. This requires careful editing and rewriting.

Finally, "image" and "poignancy" mean that a poem should be sensory and emotional. "Image" means that a poem should be a series of sensory images and symbols, rather than a series of abstract ideas or summaries of feelings. Often a poem will try to develop no more than one image per line.

"Poignancy" means that these images should develop in the reader a strong and often special--even delicate--emotion that fills up a reader's imagination. Notice the difference in image and in feeling between the following two versions of a poem:

| We had a great time on the ship at night, but it felt very good to come home, too. |

The ship rode starlit waves as we danced like the foam; then warm arms at home wrapped around us again. |

These six elements--rhythm and rhyme, brevity and tightness, and image and poignancy--are basic to many forms of literature; but they are found especially in poems.

Divisions of Literary Criticism

Professional literary critics often are loosely associated with a certain "school" of criticism. A "school" of criticism is a loosely connected group of critics who approach the criticism of literature with certain basic beliefs in common. Multicultural criticism, for example, begins with the belief that most literary works that claim to be great literature must have a multicultural focus. If they do not, then they are the opposite: they are an expression of one culture's dominance and perhaps even prejudice against other cultures. A multicultural critic might observe, for example, the works of John Steinbeck, author of such books as The Grapes of Wrath, The Pearl, and The Winter of our Discontent. Such a critic might argue that whereas Steinbeck does seem to discuss only white, middle-class American culture in some individual books (e.g. The Winter of our Discontent), still in a majority of his other books Steinbeck deals with several cultures, economic levels, and even races, either individually or as they mix with each other. Therefore, a multicultural critic might conclude, Steinbeck meets the test of being a multicultural writer.

However, another type of literary critic might negatively criticize Steinbeck's literary works. The feminist school of criticism, for example, believes that any literature that defines itself as great literature must show women as strong human beings in their own right who are capable of growth, independence, and living a complex, rich, and rewarding life. Any literary work that does not express these values directly or indirectly cannot claim to be great literature, for it echoes instead the negative values of sexism, male authoritarianism, and male violence.

From a feminist critical standpoint, Steinbeck's novels can be criticized at least to the extent that they rarely show female characters who are well developed, rich, and complex. Steinbeck does not seem to consciously degrade women in general in his novels. However, most of his characters are men, the worlds he creates for them are places where power, authoritarianism, and violence exist, and therefore his novels may be called "masculine" novels at the least and, possibly, antifeminist novels as well.

There are many other schools of literary criticism as well. If you were to place two critics from each of five different literary schools in the same room, you might find that all ten often would disagree with each other in interpreting the meaning and value of any single literary work. However, the very multiplicity of critical viewpoints adds to the richness of the discipline called literary criticism, and allows for constant reevaluation of the most basic and important values the world attaches to its storytellers and their literature.

Here are some schools of literary criticism:

HISTORICAL AND BIOGRAPHICAL CRITICISM: Much literary criticism for several hundred years was composed of historical, biographical, moral, religious, and philosophical criticism. The first of these two, historical and biographical criticism, still is a common approach in elementary and secondary literature classes: one examines the historical events surrounding or related to a literary work, or the biographical details of an author's life as they impinge upon the literary work that he or she has written. As a basis for developing a viewpoint about a literary work, such criticism is a good start. However, many academic literary critics wish for much more.

MORAL, RELIGIOUS, AND PHILOSOPHICAL CRITICISM: Those in the academy who used go beyond historical and biographical criticism found few tools with which to do so. The primary intellectual tools available to them were to use moral and ethical theories, the beliefs of religion, and the beliefs of philosophy to explain and discuss literature.

FORM CRITICISM: In the late nineteenth and first half of the twentieth centuries, newer forms of criticism arose. One of these was form criticism, and it developed as a reaction against earlier, traditional forms of criticism that didn't seem to have much to do with explaining the quality of storytelling or the other artistic elements of literature. Form critics argue that one should judge a work of literature solely on the basis of its artistic merits. Form critics discuss only the elements of a literary work and how they are used well or poorly, and usually avoid discussing anything to do with the author's background, the historical times in that the work of literature was written, or any theories of psychology, sociology, politics, et al. and how they affect or are used in the literary work. None of these, say form critics, are relevant to examining the elements of the work itself. This type of criticism arose as a reaction against oversimplification, especially in historical and geographical criticism.

PSYCHOLOGICAL CRITICISM: Psychological criticism arose in the nineteenth and early twentieth century as an alternative to traditional forms of criticism. It is based on the insights of psychology. Psychological critics take the position that literary works demonstrate principals of psychology and therefore can be analyzed to show how well or poorly basic tenets of psychology are expressed. In its most limited sense, this school of criticism is connected primarily with the theories of Sigmund Freud, the primary founder of modern psychology. However, in its widest sense, psychological criticism contains other schools of thought as well: Jungian archetypal criticism and mythological criticism (both of that look for the basic commonalities of the human race's symbols in literature, symbols such as rituals of birth, marriage, and death, and the mythic gods and goddesses of the world); anthropological criticism (looking in literature for themes typical of cultures throughout the world and time such as the sacrificial hero, the earth mother, etc.); and other psychological theories--Adlerian, transactional, etc.

POLITICAL & SOCIAL CRITICISM: Political and social criticism became popular in the twentieth century and is related to--and an improvement upon-- the more traditional forms of moral and philosophical criticism. Like these earlier criticisms, political and social criticism looks at the broader beliefs and systems such as democracy, authoritarianism, and communalism that link people together into workable systems of government and action. Political and social critics look for examples of various forms of political and social systems in literature. The Marxist school of criticism is one of the better known sub-groupings of these types of criticism.

FEMINIST CRITICISM: Feminist criticism is an offshoot in some ways of both psychological criticism and political and social criticisms: as women became more empowered in literary and academic circles in the latter part of the twentieth century, there was an increasing call for a gender-related form of criticism that not only negated the sexism, authoritarianism, and violence of much of male-oriented and male-written literature, but also described positive feminist values that exist in the literature of many women and some men writers. Some examples of subgroupings of this school are Marxist feminism, minority feminist studies (i.e., black feminist studies, Chicano feminist studies, etc.), lesbian studies, and psychoanalytic feminism.

MULTICULTURAL CRITICISM: Multicultural critics judge a literary work on how well or poorly it exemplifies the people and their values in other cultures. Some branches of multicultural criticism include Afro-American literary studies, Latin American studies, and many other racial and cultural categories. It also sometimes is understood to include gender and feminist studies. Multicultural criticism in all its varieties is among the newest schools of criticism.

OTHER CRITICISM: Other forms of criticism exist, too. Traditional Aristotelian criticism looks at the formal categories of literature described thousands of years ago by Aristotle, linguistic criticisms examine the uses of language in literature, genre and rhetorical criticism look at the structural parts or building blocks of literary works, reader-response criticism examines readers' responses to literature, and many discipline-specific sub-schools (new historical criticism, genetic criticism, existential-philosophical criticism, etc.) develop their own particular literary criticism using the intellectual tools of their discipline.

The Purpose of Literature

What is the purpose of literature?

First, it has a very important function within the context of society and history. Literature quite simply is a world changer. The present world civilizations are based on communication. Histories, languages, cultures and arts--everything involved in the humanities depends on and flowers through communication. Literature sets the example both in content and in style for the finest communication that can come through voice, paper, or visual play. Study the literature of a race or people, and you have studied the marks they have tracked through time. It is impossible to know most races or people in history without reference to their literature. Their literature, oral or written, is them, and they are their literature.

Another purpose of literature is entertainment. This is easily forgotten in the rush to consider the intellectual, ethical, and social importance of various literary works. However, part of the definition of "great literature" is that it has been able for many years to entertain people very well indeed. Such entertainment might cause horror and sadness as well as--or instead of--laughter and excitement. Whatever the emotion, great literature gives pleasure.

Another purpose of literature is self-expression. Again, this purpose becomes easily overlooked in the commonly held belief that you and I, the readers of literature, could "never write like that." It is true that we may never write great literature. However, all human beings are capable of expressing themselves in the symbols of language, and literature--be it high literature or low--is an exemplar of such self-expression. Avid readers often feel the urge to become writers themselves, and everyone has his or her own story to tell, even if it is just for family or friends or even just an audience of one--the reader himself. Such self-expression is healing, thoughtful, powerful, explorative, and interesting. And reading great literature offers readers the tools for such self-expression: one learns the elements of literature, and then he or she can practice them.

A final important purpose of literature is that it helps people discover themselves. It gives readers insight into their feelings, thoughts, pasts, futures, and ultimate values. In a sense literature is perhaps the oldest and most common form of psychology, one available to readers of all abilities and interests. And if literature is like having a psychologist on the shelf, ready to take down and read whenever one wishes, great literature is like a great psychologist, giving important insights to readers that were previously unavailable to them.

Becoming a Literary Critic

In the field of literature, there are those who create it and those who review and examine it. Reviewers and examiners of literature play a function similar to historians: they are the people who evaluate what has happened in a piece of literature once it has been written. Often they also determine the degree to which it will be accepted or rejected. If, for example, a literary work is not accepted for review by media critics, often the literary work is never heard of again. Everyone has heard stories of some literary work that the critics ignore, but it becomes popular through the "underground"--by being passed from person to person. This happens on occasion. However, the great majority of literary works that become even somewhat known must not only be accepted by editors but also by media critics. And those works of literature that become part of the accepted "canon"--the group or groups of literary works that educational institutions recommend for reading and teachers choose for teaching--such works of literature usually are analyzed and evaluated in dozens and even hundreds of articles in scholarly and professional teachers' journals.

Those who are professionals in the field of criticizing literature have two primary methods of communicating their analyses. One can understand how professional critics think by looking at each of these two primary methods of thinking.

The first method is used by media critics. It is a literary review. Though there are many variations of literary reviews, basically the reviewer works in three stages or steps as he or she describes the literary work, interprets some of its meanings, and then evaluates. Here is a summary of each of the three steps, then a brief example of how these work:

DESCRIPTIONS: Observe and describe the literary work factually by its elements and structures. Start with the simplest elements such as language use (rhythms, rhymes, types of words chosen by the author), types of description (use of the five senses, colorfulness or lack of it in describing characters and scenes, etc.), and tone and style (humorous, serious, highbrow, lowbrow, ironic, pedantic, light, heavy, etc.). Then move to the larger elements: obvious symbols, secondary and main characters, plots (external and internal), subplots, and/or overall structure.

INTERPRETATIONS: Suggest possible interpretations that both readers and the author might possibly have of the literary work. Interpretations may include less obvious and/or overall symbols, competing possible meanings of characters, a variety of competing themes or meanings that readers may perceive in this work. Competing interpretations are good.

EVALUATIONS: This is what media reviewers are famous for. Evaluation means, basically, what is good and bad about the piece. Evaluatve questions might include such subjects as the ethical or moral value of a literary work, its aesthetic or artistic appeal, what it will do for or to people, its honesty or accuracy of portrayal, its emotional appeal, and whether it is essentially ugly, pedestrian, or beautiful.

Here is the example using the system above:

Descriptions: The Color Purple by Alice Walker uses colorful visual and physically sensual images in particular, with some emphasis on vivid slang to convey the sometimes brutal, sometimes beautiful life of a woman who is abused as a child and young woman. The tone is down to earth, almost overwhelmingly so, yet the style, while containing simple sentences that makes the book easy to read, flows smoothly and often takes flight, wringing emotions out of characters and the reader alike. Purple becomes a central symbol for the life of the main character and of women (and men) in general, as do such moving and central physical objects as blood, fists, rocking chairs, and a host of other details. The main characters are.... Memorable secondary characters include.... The basic plot of the story is....

Interpretations: The obvious theme of this novel, many would argue--feminists in particular--is that women (white as well as black) can rise above their abuse at the hands at men and become whole again, no matter how deep and how sever that abuse has been. However, others might argue that this theme of rising above pain is not limited to women but exists for men, too. Some would argue (and the community of African-American males in this country have done so) that this novel portrays black men as insubstantial and unappealing power mongers who must be put in their place. Yet a closer look reveals that strong men also exist in this novel, and even the weak men may become more whole with help. Other interpretations include....

Evaluations: The impact of this novel may be so great that it is difficult to calculate. Not only does it give voice to a segment of society too long voiceless (or at least too long oppressed to be heard well)--African-American women--but also in its sweeping simplicity it will attract and powerfully affect both men and women of all races and generations. Will the impact be good? Some argue its portrayal of black men is unfair, but this critic thinks this evaluation is incomplete at best, and unfair at worst: if Tom Jones and his like can cavort so freely in literature, it also is reasonable and just to see the female side of suffering caused by males. This novel, in fact, becomes an ethical encouragement-- not for its negative portrayal of men but rather its positive portrayal of how women and their men eventually can come to terms with each other. Other effects of this novel are....

A literary critic who is an academic professional works differently. He or she emphasizes interpretation, and does so by choosing a particular way of viewing the meaning of a book. Then the academic critic will argue for this interpretation. For example, two different academic critics might argue that THE COLOR PURPLE is or is not primarily a work of African-American feminism--or, for example, that the book does a good or bad job of portraying men.

Academic critics often identify with certain schools of thought within their own literary discipline. As explained above, critics may be feminist, psychological, political (especially Marxist), form critics, or one among a number of other types. Each academic critic starts with a different point of view and then tries to argue this point of view in important literary works. Here is how it is done:

A. START WITH A POINT OF VIEW. The best way to do this is to work with an interpretation that is unique or different from what others will see in a literary work. Your personal experience or personal studies may help you: for example, if you have experienced being poor, black, and female yourself, you may have some interesting interpretations to make of The Color Purple because of this personal experience. Likewise, if you have studied the sociology of poor, rural southerners in the earlier part of this century, you may have some points to make about The Color Purple that transcend race and/or gender that few other readers would perceive.

B. THEN FIND PASSAGES IN THE LITERARY WORK THAT SUPPORT THIS POINT. You can pick details from various parts of the plot or progression of the story, you can pick certain characters or certain traits, actions, or words by certain characters, you can pick symbols, descriptions, or other use of language--or any mixture of these you wish.

C. ORGANIZE THESE SUPPORTING POINTS INTO THE STEPS OF AN ARGUMENT. Make your basic, overall interpretive point in the very beginning of your essay; then start arguing using your supports, step by step, usually putting your strongest proofs first and your weakest proofs later.

Exercises

Exercise 1

Name the best book, movie, play, or poem you have ever read or seen, something that affected you deeply and even, perhaps, changed your life in some way. How did it affect you? Why? Why do you think it might qualify as literature--a work of art?

What part of culture and time was this book? That is, what part of American or foreign culture, society, politics, and geographical area does it fit into? Why-- what tells you this? How does this relate to your own culture and time, the one you are living now or that you have lived in this life?

How does this particular piece of literature fit in with your own personal philosophy? Why? How did it change, strengthen, or weaken your personal philosophy of life?

Exercise 2

If you could design a piece of great literature, any piece at all, who would you want as the hero or heroine? Why? Who or what would you have as obstacles or resistances? Why? How would these obstacles or resistances hinder the hero/heroine? What would be the very worst obstacle/resistance? Why is it the worst? What kind of emotions would you expect your hero/heroine to have? Your readers to have? Why?

Exercise 3

Use the following formula to create three different symbols of three different people or events.

______________ is like a __________ because (person/event) (symbol)

both are ____________, ____________, and ____________.

(Example: Love is like a rose: both are pretty to see and sweet to smell, and both have thorns.)

Exercise 4

Write a 50-100 word rough-draft description of a special person or event with a strong emotional meaning to you. Then try to rewrite each sentence into one or two lines of poetry. Each line should have just one image several words in length, as in the examples in the poetry section in this chapter.

Exercise 5

Start with your 50-100 word rough draft from Exercise 4 above. Rewrite it by triple spacing it (by hand or printer); then, using carats (/\) and/or arrows, add descriptions by adding single words, phrases, and or whole sentences. Add each of the five senses at least once, and nearer the beginning write--or add--the five W's of journalism that you do not already have. (You may, if you wish, check the formula example, "Jack and Jill," in the section above discussing this type of description, and copy the sentence, inserting your own applicable W's as you copy.) Finally, between the lines or in another section, add some dialogue: have two characters discussing a subject that is upsetting to them or arguing with each other.

Exercise 6

It is said that everyone has at least one great story in them--something so full of difficulty, pain, love, heartbreak, striving, or other deep feelings and experiences that almost everyone can relate to this story. What is your greatest story? Why? It also is said that to be a good literary writer, one must on some level be an exhibitionist. Why is this statement made? What does it have to do with telling your own great story?

Exercise 7

As a class, choose a short story or a poem of at least eight or ten lines to read either at home or in class. Then discuss this literary piece by examining its elements: start with the smaller, simpler elements such as language (rhythms and rhymes of words and the types of words chosen by the author), the types of description (types of five senses; use of the five W's), and the tone and style--humorous, serious, impatient, quiet, loud, intellectual, highly accessible, et al.) Record your opinions together on a blackboard--alternate opinions are valuable. Then discuss larger matters: the existence and meaning of symbols, and the nature of the characters, their depth, and their importance. Finally, discuss the most encompassing elements of all such as the plot (including external and internal), subplots, and possible themes.

Exercise 8

In small groups, construct the outline of either a critical review or an academic criticism of some work of literature--or even a movie or play--that everyone in the group has read or seen. Share this construction with the rest of the class.

Exercise 9

Name a significant problem you once had (but no longer have). Name how you solved it. You now have the basic structure of a story: person (you), problem, and solution. Write one "scene" that shows by example the problem or solution. Make your scene appear as a scene in a movie--use descriptive words, action, and/or dialogue to show exactly what happened in just one place at one time.

Bibliography for Literature as a Humanities Subject

Abrams, M.H. A Glossary of Literary Terms. 6th ed. Fort Worth: Harcourt Brace, 1993.

Drabble, Margaret, and Jenny Stringer. The Concise Oxford Companion to English Literature. New York: Oxford UP, 1996. [Dictionary.]

Goodman, Lizbeth, ed. Literature and Gender. New York: Routledge, 1996.

Green, Keith, and Jill LeBihan. Critical Theory & Practice: A Coursebook. New York: Routledge, 1996.

Guerin, Wilfred L, et al. A Handbook of Critical Approaches to Literature. 3rd ed. New York: Oxford UP, 1992.

Pack, Robert, and Jay Parini. Writers On Writing, A Bread Loaf Anthology. Hanover: Middlebury CP, 1991.

Valade III, Roger M. The Essential Black Literature Guide. Detroit: Visible Ink,

1996.

Online Resources

If you'd like to find free online literature, a vast body of free classics are available:

Literary Books:

Or search for your book or author by name and the words "read free": (e.g., "read free Shakespeare").

Poetry:

Search "read free poetry" or "read free classic poems."

Short Stories:

Search "read free classic short stories."

Movies:

Often the fastest way (and the most enjoyable for many people) is experience a story by watching a video. This is one reason why movies and plays are so popular: they give you a book-length story in one to three hours of time. For this reason, you may want to see some classics of literature by watching the movie versions. To search for movies, simply use the title and/or author of a book and add the word "movie" or "video": e.g., "free movie Romeo and Juliet."

Live Plays:

A great way to see literature is to watch it performed live as a play. Great

plays are great literature, and sometimes great literary novels/books are made

into great plays, as well. See the end of the "Performing Arts" chapter in this

textbook for information about finding and watching plays.

---

---

*Image in Chapter Title: “Picture Writing of the Ojibway Indians” in The

Americana, a Universal Reference Library, 1098, Wikimedia Commons.

https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?sort=relevance&search=red+riding+hood&title=Special:Search&profile=advanced&fulltext=1&advancedSearch-current=%7B%7D&ns0=1&ns6=1&ns12=1&ns14=1&ns100=1&ns106=1#/media/File:Little_Red_Riding_Hood_-_Project_Gutenberg_etext_19993.jpg.

Retrieved 27 Mar. 2020.

Most recent revision of text: 29 Sept. 2020

|

---

|

|