|

Experiencing the Humanities

A Web Textbook

|

|

|

Experiencing the Humanities

A Web Textbook

|

|

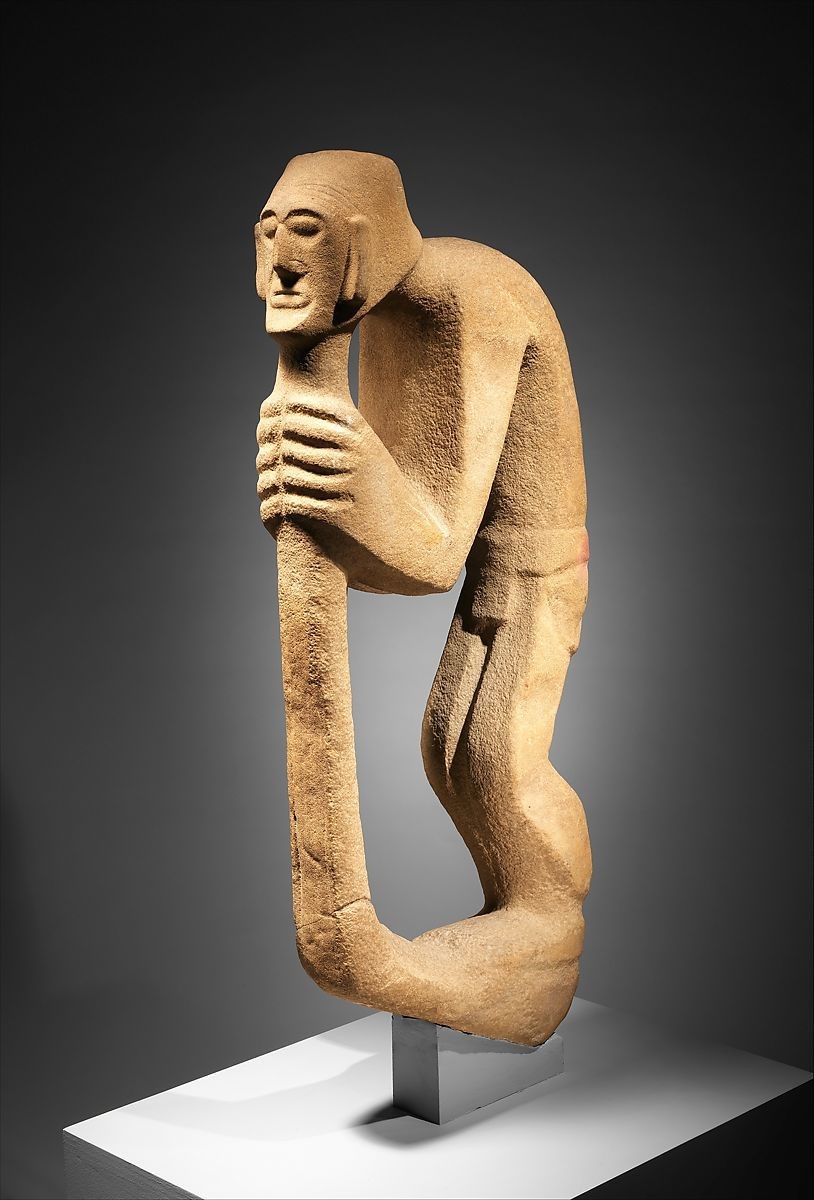

Hunchback, Sandstone*

Chapter Fifteen of

by Richard Jewell

Introduction--Will Art Change?

Is the sculpture above modern or even contemporary (recent)? It has a

modern/contemporary flow of line, it is

of a common working person, it shows semi-nudity, and it obviously is, in part,

an abstract because the pillar on which the figure leans is flowing in an

abstract manner into the

worker's legs. All of these would, at first glance, suggest the figure above is

modern or contemporary art. However, this figure actually was carved in stone in Mexico sometime

in the tenth-twelfth century CE--it is roughly a thousand years old.

Does all art remain the same? Yes and no. In some basic ways, it does have

similar characteristics throughout the ages. Its basic forms continue to be

used. Artists keep representing nature, human beings, and sounds from nature and

humans. And the practical arts--such as buildings and drinking cups--continue to

require similar shapes throughout the ages.

However, there are other changes, substantial ones, that have happened over the many thousands of years that the arts have existed, and this has been especially true in just the past 500 years. These changes may even be increasing faster as we approach the future. There are several notable events and movements in the world of the arts that will be important for their future. Four of these are as follows:

continuing trends (exemplified by the nude)

digital arts

more artists as professionals

interactive art

"Past and future trends" are for all the arts; however, a discussion of the historical and contemporary nude in art helps us better see the future of all the arts.

"Digital arts" are TV, video, telephone and computer arts, and related activities. They are new in history.

"Professional artists"--those paid to be artists--have been few in number until the 20th century. Our higher standards of living have created a whole social class of paid artists (as already noted briefly in chapter two concerning the new creative social class).

"Interactive art" is a kind of art in that audience and art object or performance interact with each other. Interactive art in the future may increasingly dissolve the boundary lines between audiences and the art objects or performances they view.

Continuing Trends (Exemplified by the Nude)

Certain trends in the future of art will continue. These are well exemplified in the history of the nude figure in art. The nude figure has been--and still is--a very popular subject in the visual and sculptural arts for at least twelve thousand years. Here, three sets of nudes show continuing trends in the arts, as well as how these trends may change and combine in all the arts in the future.

The nude on the left, below, is about 4300 years old. The set of two, together in the middle, are famous late-Middle Ages/early Renaissance (1507 CE) prints. The one on the right is by a contemporary professional artist who has had exhibitions and made album covers and music posters, and whose background art appeared in the Elton John Performance at the 2020 Academy Awards.

Left. Idealized Egyptian.

Striding Man,

ca. 2289–2246 B.C. Metropolitan Museum of Art.

www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/548488.

Middle:

Adam and Eve, Albrecht

Dürer, Museum

del Prado, Oil on Panel, 1507,

https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=150385.

Right: Figure Study, Erin Goedtel, Oil on Panel,

2003,

https://eringoedtel.com.

Used by permission. All rights reserved.

Images retrieved 26 Mar. 2020.

The nude figure in art has undergone a profound transformation in Western culture over thousands of years. In very ancient times when the Mother religions were predominant (10,000-1000 BCE), many figurines--sometimes called Venus figures--were made. Sometimes they depicted female goddesses, but more often they were depictions of nude women, often very heavy; the figurines themselves were small, squat, and pointed at the bottom so they could be pushed into the soil. This, people believed, helped increase the Goddess energy of gardens and fields for greater fertility. Sometimes they were placed in a home where a woman hoped to become pregnant. These practical art sculptures usually were of female images of pregnant and/or well-fed women--in short, women who were successful in having children and in growing plants.

However, when the Western religions of the Father and multiple other gods in heaven (for example, Zeus, Odin, Osiris, Ra, Baʿal, Mithra, et al., 3000 BCE-500 CE) came into existence, gradually nudes in art became the province of males, especially in early Greece and Rome. In these times of the Father religions, women were less often shown nude in art because they were not considered as powerful or as attractive as men. The male nude figure was a very important idea in Greek and Roman art because it showed the physical prowess--the musculature, the heroic face, the warrior stance--of powerful males. Men in those times often were nude, or in all but a binding to protect their genitals, in athletics--such as the early Greek Olympics--and even sometimes in combat. The photo above is of an early example of the heroic age of male nudes, depicting the idealized body of an Egyptian male.

Gradually, in the West in Europe, nudes disappeared in most art during the medieval ages, only to return, once again, in the renaissance in depictions of nude male gods. During this time and after, female nudes--as goddesses and other mythic women--also slowly began to come back into art. The strictures against female nudity were greater in medieval times than against male nudity; as a result, women in the renaissance--even more so than men--had at first to be depicted as parts of Biblical stories, and then, later, mythological stories. Artists used models, but they gave their models religious or mythological names, such as in the paired set of Adam and Eve above by famous artist Albrecht Dürer.

It wasn't until the 1800s and later that artists could simply choose and paint a real woman in the nude as a legitimate part of art. Now, artists continue to paint nudes of both men and women as one of the favorite subjects of art. This modern trend is depicted on the right, above, in Figure Study by contemporary artist Erin Goedtel.

All three sets of works of art, above, can help us understand the movements of trends. They help depict how art is staying the same but also changing from ancient to modern and into the future:

(A) More stark realism: As Western culture moved into increasingly modern times, the "nude" form gradually became, in many works of art, what some art critics call the "naked" form--as in the contemporary painting above on the right. Whereas the "nude" form was more idealized as a type of perfection, this newer style of "naked" form is the result of showing more realism, more detail, and more individuality in the painting. This is one of the major trends of the future in art: increasing individualism, stark reality, and detail. People want to know what they are looking at and to not have the harshness and plainness of life glossed over by typically always-beautiful scenes.

(B) More color: However, the color and style depicted in the painting above on the right also show a very different trend: one toward much more and brighter use of color, "colors that pop," as some art reviewers say, colors that are splashy, fun, and wild. And the contrast between 2500 years ago, 500 years ago, and today in the three sets of paintings above is obvious.

Colors that are the rainbow, colors that are so big that they take over some works of art, colors that literally seem to be bleeding or wet or vibrating like energy--all of these are trends that are partly cultural desire for brightness and energy, and partly because of mediums such as better pigments and a variety of substances used. Our cultures want more color, more "pop," and likely will want it increasingly as the future develops.

(C) More abstraction: However, if you observe how the colors and some of the background are handled, the far background is indistinct, and even the other colors don't follow perfectly rigid lines. There is an abstraction in the coloring, one that lends itself to impressionistic emotional response, a more general spreading out of color and thus of feeling. This, too, is another likely trend in art: to be more accepting of abstractions in art--whether paintings, music, sculpture, or other forms. We as a world culture, are becoming more sophisticated in what art can deliver to us, and we are becoming more understanding about what some abstractions can mean.

It is well worth remembering that when the first moving pictures were shown, some audiences angrily booed, waved their fists, and even threw chairs and other objects at the screen, so great was the shock of going from a three-dimensional real world to a depiction of it in moving two-dimensional pictures. Now our world cultures have reached the point of acceptance of many abstracts in art, and we likely will continue to accept and understand more.

(D) More drama: In addition, modern artists are more interested and willing to show parts of human nature that were either forbidden or tamped down in art--and in general cultural expression of any kind--in medieval and even renaissance times. The figure in the painting above on the right, for example, shows much more emotion, and a mixture of them, than the figures in the first two sets of paintings.

Other examples of greater drama exist especially in the digital arts, but also in any of the visual, sculptural, and performing arts. For example, human nudity and sensuality are much more acceptable and much more on display. In music, 19th-21st century clashings and atonalities--lack of harmonies (especially in heavy-metal and thrash rock, for example, though not exclusively)--are symbolic of internal emotional disruption, disarray, and pain. Literature and the visual arts are more willing to describe and show blood and guts, intense emotional anger and fear, and exceedingly intimate feelings and acts. These increases in drama in the arts likely also will continue and expand as our culture around us finds it more acceptable to recognize and talk about them.

(E) More technology: The Egyptian man on the left, above, is striding with no sense of background and a stylized haircut that could have been done thousands of years earlier than he was carved. The pair in the middle, above, are Adam and Eve with an appropriate background of the tree and the snake in the Garden of Eden in the Holy Books of Christianity, Islam, and Judaism: a very classic subject, religion, for the era of late Medieval/early Renaissance times in which they were painted--and a background far earlier than the time of the painting itself. However, the sunbathing subject on the right, above, has modern technology surrounding her: a colorful umbrella of metal spines, her eyeglasses, and the lounging chair in which she sits.

Thus the arts evolve in what they show: in this instance in Western art, they have moved from the Middle Ages, when most Western paintings were culturally expected to be of religious, mythological, or royal subjects; then to several centuries of showing and even, eventually, encouraging natural backgrounds and normal human subjects; and finally to our present centuries when showing industrialism and, now, technology, is an important element of "realistic" art. In the past five hundred years, you could argue, the subject matters of Western art has evolved from Adam and Eve to a fantasy future--a great leap for humankind of tens of thousands of years.

(F) More combinations of trends: Finally, one especially noticeable quality of the portrait above on the right is that the all four of these trends, "A"-"D," are combined in this one painting: stark realism, bright color, abstractions of color and form, and darker emotional feeling. In former centuries, works of art were more careful to limit such combinations. One of the most important future trends in art is the continuing breakdown of hard and fast categories in art. Artists are combining as many different styles, forms, messages, and mediums as they can. There are sculptures within plays, and plays built around sculptures; art painted or written on buildings; music combined with stage plays (i.e., music videos); wild colors in frightening or angry performances.

Those who make works of art want, as their ultimate purpose, to convey as much artistic language--the language of feelings--as they can in strong and varied ways. Artists in all the arts are learning to do this increasingly--in music, dance, sculpture, architecture, the visual arts, et al. And as the cost of the mediums for art forms--paints, sculptural material, digital software, and others--decreases, the more these artists can experiment.

All of these five trends have been gradually developing since the dawn of art in scratchings and drawings upon cave walls and in the grunting, chanting songs and dancing words uttered around campfires fifty to one hundred thousand years ago. Art and culture both innovate, and they reflect each other as they do so. Over the thousands of years of human civilization, art and culture move to ever newer and, often, more interesting states of expression. That will continue to be true with all five of these trends in the future.

Digital Revolution

Marshall McLuhan, a social commentator, developed a viewpoint in the 1960s that the most important influence of TV (and now of computers and videos) is not the contents of what it shows, but rather its affect on the way we see and feel.

What McLuhan said is that where communication at a distance is concerned, our modern TV/digital generation communicates by seeing more than one piece of information at a time on a screen. Instead, a screen has many visual points of reference. McLuhan says this is very different from how pre-TV generations communicated. They used mostly oral communication: they shared words by radio and telephone and, before that, by writing and reading texts--which tend to be created and used with "oral" thinking--a flow of words and sounds--in our heads. This flow of words and sounds involved one sound at a time, no matter how fast it might go. However, an image from a TV or computer monitor involves many images at a time, dousing our brains with many more signals than they receive in listening to a sound.

Of course, we still do use texts, radios, and phones for talking, just as in pre-TV years. And, as McLuhan points out, many of the uses of visual electronics may just amplify the old way of oral communication, one sound and one small specific image at a time. However, the point McLuhan makes is that our TV/digital generations also are, increasingly, learning to use a different form of thinking. In our TV/digital age, we communicate more by visual thinking--a flow of multiple images in our heads--than by just oral thinking that is just one sound at a time.

This means, for example, in the arts, that a significant difference may exist between hearing someone describe a person or story on the one hand, while on the other hand actually seeing a moving image of that same person or story. The oral description takes much longer; the visual image shows multiple parts or elements of the person or story in each second. And what happens if we place both types of thinking together: what if we let both the sounds and the images happen? The result is much more powerful, especially in a moving image, as there is so much more to see than to hear. This was the point McLuhan was trying to make.

Some arts will be less influenced by this change in thinking from sound to digital imaging. For example, story writing and music will remain in many ways the same in terms of how people absorb them. But other types of arts already have become dramatically affected, such as paintings and performed arts. They now can be shared more readily; more important, though, it is so much easier and so much more common, now, to make a visual and sound story that moves--as in movies, videos, and everything like them. The digital arts don't just make seeing pictures more possible: they make watching and listening to the performing arts available to everyone everywhere on earth. What used to be staged performances for a few thousand at a time in any one geographic location now available to millions, even billions of people anytime, anywhere.

As a result, our society, our culture, and our artists are becoming increasingly sight-oriented thinkers and creators. McLuhan argues that our generations think more in images, however fleeting or fast, than did most of the educated people who grew up before the existence of TV.

This means that the visual arts--and art forms that can be turned into visual images--likely will receive more attention now and in the future than ever before. And art forms that rely on oral communication, such as creative writing and music--will have more of an unspoken but more emphasized visual background component to them--that is, their creators/composers will use more description than before in stories and have more images in mind when composing music than in past centuries. Society's change to a more image-dominant way of thinking also likely will mean, given the nature of TV, computers, phones, and video, that for the first time in history, the art forms combining sight and sound may become the dominant art forms. In many fields of art, digital images and videos may do for millions of us what only live performances used to in previous centuries. And this will slowly but surely change not just the arts but all of our cultures and civilizations in ways we can barely imagine at this time.

In addition, we have reached an age in history when we now can sculpture light itself through TV, computer, phone, and video monitors, and show color and line moving through time. We also can show abstract representations of light, color, line, and sound in interaction with each other. Some artists already have worked in these directions, and the 21st century and beyond may see the first groups of great artists in this abstract or expressionist medium.

Three-dimensional digital transmissions called "holographs" also now exist, from laser and other technological inventions. These holographs may, in people's living rooms, gradually replace two-dimensional TV, computer, and video presentations on two-dimensional screens. Someday far in the future, we will have holographic (three-dimensional) videos.

Even now we are developing simple versions of virtual reality. Virtual reality is a form of computerized reality that is being developed by a number of companies and agencies. The Pentagon, for example, is using it for human control of robots working in outer space. Another example is VPL, a licensee of the Nintendo power glove, for simulated three-dimensional computer programs using 3-D helmet-glove sets for computer games, architectural models, and surgical training. The helmet has computerized visual images that "allow" one to see an image three-dimensionally, and the computerized glove allows hand control of the three-dimensional image. As these are further developed by this and similar companies in the 21st century and beyond, we will see virtual reality become increasingly popular and often used in business, with gamers, and in a number of leisure-entertainment fields.

More Artists as

Professionals

Another part of the arts in the future is that increasingly greater wealth in most countries is allowing greater numbers of artists to make money in the arts. This newly rising class of artists in society is a professional class, like other types of people in other businesses, that is becoming increasingly accepted in our cultures.

In many societies and cultures in the past (and in a large portion of the undeveloped world in the present), the artist was looked upon as useless and costly to society: unable to grow food or repair or build things, less interested in forming a traditional family that worked for its living, and not really fitting into a society in which almost everyone performed an immediate practical function. Throughout history, in fact, artists have been unaffordable to most individuals and most of society. It almost always has been only the richer classes--royalty, priests, and sometimes a small but developing middle class--who have supported the fine arts and artists. And usually these richer groups of people had much less money, patience, and willingness to support the fine arts than our society does today.

In those earlier days, a lesser-known class of "public artists" (those who developed their art by appealing more directly to the public)--e.g., strolling minstrels, artisans who crafted pots and silverware, and village storytellers--worked for just enough pay in food and money to survive, moving from village to village. These artists helped develop public art that, over a period of time, has come to us through the centuries in the form of ancient fairy tales and legends, old songs, and a history of fine craftwork.

However, in societies where a strong middle class exists--such as in our own developed countries or even in parts of ancient Greece or Egypt--people have been able to spend more money and time on the arts. Artistic activities such as watching TV, reading books, listening to music, and attending arts events become a significant part of such societies' activities. When art is so significant, the artist becomes a respected professional who is looked upon by the society as one of its contributing workers. Creativity becomes a commodity for which some people are well paid--and to which many more people aspire.

We may expect in years to come that as leisure time in the form of television, movies, music, and other arts becomes increasingly valuable, professional artists in larger numbers may begin to achieve the respect and pay that educators, government workers, and religious workers now receive. This changed status of the artist as professional is producing more people interested in the arts as a profession--and more interest in the arts themselves.

There also is a continuing dilution or "popularizing" of the arts, a process of making artistic pieces more appealing to more and more people. Critics of these changes say that we are becoming sloppy in who we call an "artist"--for example, they argue that professionals are making too many poor movies, paintings, videos, and other forms of popular art just to appeal to people's money rather than a true sense of deeply felt "high art." And that such artists actually are just craftsmen and craftswomen who make money by capitalizing on artistic trends. However, this has always been true. In the past, poor storytellers and mediocre singers would go from village to village, telling stories of fairytales and of works of art like the Iliad and the Odyssey to audiences that could read neither the written word nor notations on a sheet of music. In those times, poor copiers of great paintings would copy them onto simple pots and baskets in order to make money. The only difference between then and now is that as the audience and money for art has increased, so have the number of poor copies of art developed along with good art.

In addition, as has happened throughout the ages, good art is not always recognizable in its initial setting of time and place. It is useful, perhaps, to remember that many works of art were not recognized as such--or were recognized as merely of entertainment value only. Among such artists are Shakespeare, Dickens, and Van Gogh; works of art such as Pet Sounds by the Beach Boys and Swan Lake by Tchaikovsky; and art forms such as plays, rock and rap music; and comics as graphic novels. All of these historical patterns will continue to be just as true in the future of the arts, with a similar percentage of the population--and a much larger number of individuals. Often, what seems today's simple leisure-time entertainment can develop into tomorrow's great art.

What does all this mean for future artists? The situation is, at once, encouraging and troubling: encouraging that great art can continue following new and even radically different forms; however, troubling for artists who want to make a living from creating art that may or may not be saleable. Being an artist will continue for many to be a precarious profession. In addition, there will long continue to be some who are successful enough to be full-time artists, some who can only be part-time, and some who will make no money at all. Popularity of the artist--with or without quality--is only part of the reason. Other reasons may include whether an artist's creations must wait until a future generation to be recognized as excellent art, whether the subject matter (rather than the artistic qualities of a work of art) is appealing or unappealing, and a number of other qualities.

However, what is clear is that more people are making more art with each new step forward in society in leisure time, and as a result, society has a larger number of excellent artists and art productions from which to choose. If the history of art and artists in society is any guide, this will continue to happen as society itself becomes gradually wealthier for purchasing art and/or with more time on its hands for creating and collecting art. And with this increase in wealth and time will come an increase in the importance of and respect for the artist and his or her product in our society.

One of the ways in which the profession of being an artist is changing has to do with both the increased number of artists and the greater acceptance of (and financial payment to) artist. With more artists and more money for them, professional artists are, increasingly, forming groups to help encourage and solidify their place in society. There are many professional organizations of artists, now from national to local levels, much like professional guilds for the different types of workers were started in late medieval ad renaissance times by middle class craftsmen and middlemen to improve their lot and share knowledge. Similarly, some artists' organizations, such as in the Hollywood, work together to establish pay levels for themselves; and some organizations, such as many local and regional painting and writing organizations, develop seminars and courses for community members developing their artistic abilities.

In addition, more artists than ever are collaborating on works of art, especially in fields such as theater and its offshoots of movies and TV/video programs where there always has been a certain degree of collaboration. Even now, for years, SAG (Screen Actors Guild) and film’s National Board of Review provide an award for “Ensemble Acting.” Two great examples of this are Crash with Don Cheadle and Sandra Bullock, and (before such awards were given) Casablanca with Humphrey Bogart and Ingrid Bergman, both of which had a large number of popular and well known actors in their time. How much of their acting was interactive—among them as actors and with the director—especially when well-known actors sometimes are given more freedom to develop their lines and action? Likely, as more ensemble performances are developed and the authoritarian rules of auteur vs. actor become richer and more subtle group interactions, instead—when practice for performances becomes more social event than rigid production—we will see more interactive art develop among artists. We can see this trend, too, in rap music when one artist is "featured in" another artist's video. It also exists among the teams of digital artists who, together, create animated films. In addition, the tradition of collaboration between editor and writer has long been important in the world of fiction writing, as have collaborations in popular music between singer and songwriter, singer and backup musicians, and singers in bands that collaborate to create and develop their songs.

Collaboration does not mean a loss of quality, just a greater variety of quality--and with more artists working, collaboration becomes a greater possibility or even a greater need to making money and sharing it. Artists are working together more, imagining combinations of different art events and activities, and becoming, in general, more social than they were able to in earlier centuries when there were so few of them. As a society, too, we are becoming ever more social, ever more knitted together, and artists are engaging in this future trend, as well.

One final condition of the future for professional artists relates to the use of immersive, five-sense holographic art that someday will develop. Artists developing such art will, increasingly, need to be ever more attuned to--but also resilient regarding--emotional and physical sensitivity. How many senses--and how intensely--can an artist evoke in holographic art before an audience becomes uncomfortable? How much can the artist himself or herself stand to develop without going crazy? What will happen in society (and to artists) engaging in edgy five-sense holographic art? What limits will society create, especially for art that invokes "forbidden" feelings and experiences?

And one final warning to artists, and perhaps to all of those who want their art raw and untamed, is the rise of two other classes of professionals: art organizers and art critics. The organizers are those who make a living leading arts organizations, museums, musical groups large and small, and arts events. The critics often are newspaper, television, and online journal people who critique art. In the early part of the 21st century, most of these people are, or have been, artists themselves, and so they are sensitive to both the tastes of the art-buying public and the sensitivities of artists themselves.

However, as the profession of art increases in number of people and the amount of money that changes hands, both leaders and critics may become a business class of their own with ever less knowledge of what artists actually do. This has already happened, for example, to much of higher education, in which leaders are no longer former teachers but rather a professional class of businessmen and women.

As this happens with art, art will become increasingly money-oriented with less attention to high quality and innovation. One already can find phrases relating to this: the "music industry," "Broadway hit makers," "Hollywood," and similar money-oriented business groups. On the one hand, the future of art does, in fact, depend in important ways on organizations bringing more more wealth to artists. However, on the other hand, a good future for art also must often rely on small, groundbreaking, stereotype-upending artists--as individuals and in small groups--for art to flourish best. While large organizations can help bring more money, they also can make art more about money and less about creativity. creativity.

Interactive Art

"Interactive art" is art that interacts with its audience. One example is of actors and actresses who talk with their audience during a play. Another example from literature is of children's story books that require readers to fill in the names of characters or other parts. Interactive video is a third example.

"Interactive art" is art in which the audience interacts with performers or the work of art itself, thus affecting the outcome:

1. audience interacting with

2. performers or work of art

3. affecting results

Interactive art is relatively new in the world of the arts. There always have been performers such as magicians and traveling performers who have involved audiences in their performances. But only in recent historical times have critics of the arts seriously continued discussion about whether interactive art is true art.

Is interactive art true art? Can a play, a story, or a video display be considered true art if someone has fiddled with it other than the original artist? Is not such art really more like a craft or game instead, or just an exercise or experiment--not real art?

These questions are important not only because more art is becoming interactive, but also because they help us define some of the deepest meanings of what art is and how it is perceived by by a person. In addition, questions about interactive art may very well define some of the great battles in art of the future--battles that younger generations of artists are only beginning to fight now. This is because those who define art also often decide who will get the money and freedom to work as an artist. If interactive art is not considered a true art form, some of our best creators of this art form may find themselves unable to continue serious work. Interactive art may be, in fact, one of the most important forms of art to be fully born in the twentieth and twenty-first centuries.

In a way, it is possible to argue that all art is "interactive." Take a painting, for example. Doesn't a painting require the eyes of the viewer to perceive the colors, lines, and shapes of the painting. This leads to many interactions of subatomic particles of light traveling between painting and viewer.

However, this type of interaction involves only the first of the three parts of our definition above. Only the viewer is doing any real interacting. The painting is not reaching out to the viewer in any way.

It is more arguable that the sculptural arts are interactive. We walk inside buildings, stroll through flower and rock gardens and smell or touch things, and we touch sculpture if at all possible since it is meant to be experienced by touch as well as sight. We seem to do all kinds of interacting with the sculptural arts.

However, these types of interaction still involve only the first of the three parts of our definition above, even if we do use more senses than just sight with the sculptural arts.

The stage arts often are thought of as the place or occasion for more truly interactive arts. Actors and actresses sometimes will talk to audiences and listen to them. In some stage performances, especially, perhaps, history plays, comedic routines, and performances of magic, audience members actually are invited up on the stage.

Another art form, 3-D movies and books, is similar. It is still developing. In the late 20th century, 3-D movies still were a specialty niche with narrowed, claustrophobic image size and only semi-consistent 3-D in any one shot or scene. Now, in the early 21st century, they are better, especially in small form--as in 3-D goggles--but they are not yet financially feasible on a large scale. The 3-D movies that are around are actually narrow adoptions of 3-D viewing: they require special glasses and require higher prices, and the result is not a widescreen viewing but rather a smaller than usual box.

In the future, however, eventually we will start seeing 3-D movies that are indistinguishable from 3-D stage plays: the two forms will merge so that you sit in a typical tiered-seat theater watching a stage on which real live action is happening, except that it is not real action, but holographically projected. Other physical effects may develop, too. Seats that rock, tilt, and vibrate in time with a 3-D (or regular) screen of action events already exist in large theme parks and even in one- or two-person “ride” machines in large malls. At least one theater also has experimented with delivering smells to audiences. We’ll likely also someday have tasting and touching devices in theaters. What if such devices, along with current experiments with multimedia art—such as a sculpture with music and videos—were added to museums, musical performances, and even TVs? Homeowners could change smell, taste, and touch cartridges just as they do now for printer ink.

Ultimately, the technology will exist for plugging wires from our holographic TVs into nodes on our heads. The scientific know-how for adding wiring to the outside of our heads--as opposed to planting electrodes deep inside our brains--already exists. When we can have a do-it-yourself head-plug kit for watching our video screens, such kits eventually will come with all five senses included. The Star Trek-like holodeck will be so real that you can choose to visit one in a physical space or plug it into your headgear while you sit.

How long will it take such interactions to become fully interactive? Fifty years may be a reasonable minimum, with one hundred years or more possible: after all, flying cars were predicted at least one hundred years ago and, for a variety of practical reasons, they aren't generally available, yet.

But a bigger point about 3-D performances at present, and for decades or more to come, is the question, "Does the audience actually interact directly and immediately with the performers and the work of art, which change in response to them?" In other words, holographic shows to watch are one thing, but when will be get to the point where we can walk onto a holodeck as in Star Trek and actually interact, as if it were real, with holographic characters, shake hands with them, have duels with them, and kiss them? Being able to enjoy a work of art in this way would be truly "interactive art."

Newer forms of art that are more fully interactive have risen in recent times. The electronic age has brought them. We now have wildly colorful video programs that are games with various developments possible--interactive art in two dimensions or, with cartoon-like or slightly fake but realistic humans in three dimensions--while playing electronic games. We have light display units and flexible sculptural units (e.g. a series of closely gathered pins) that react to the touch, warmth, or shape of people's hands. We have painting or drawing sets and story making books that allow for an infinite number of possible developments. Someday, if three-dimensional transmissions--holographs--become more common for TV, computers, and videos than two-dimensional video-screen monitors, we will have TV, computer, and video pictures that we can actually walk inside of and participate in.

For example, there is a scenario often used by hard-science fiction Nebula Award winner Jack McDevitt. He explains how "videos" will become holographic movies in which a viewer can choose to view his or her 3-D movies (a) in the traditional way or by having a character change to look, act, and speak like oneself or another person the viewer knows; or (b) with the viewer placing herself into the action, seeing it from a character's position in the events and hearing her own voice deliver the actor's lines. McDevitt's scenario of 3-D use with external or internal insertion of oneself likely will cause a significant shift in how people interact with their art: the options will elevate love of art both because of the thrills it delivers and the safe exploration it allows. This, like McLuhan's revolution in thinking from oral to visual, likely will create a revolution in thinking from merely oral/visual to an immersive five-senses version of thinking, imagining, and dreaming.

What about interaction between artist and audience in the actual creation of a work of art? This may be harder to foresee. The time-honored division between formal audiences, who want to hear or see great art by an individual, versus leisure audiences who just want to have a good time probably never will disappear. The traditional, formal nature of high art developed by one person (or a small group of them), which is then presented to a mostly passive audience, probably never will disappear. However, other forms of truly collaborative art likely will develop. Someday, for example, will thousands of people join online, individually, to play their clarinet, trumpet, violin, or guitar in a mass online concert for an audience of millions? What would happen if hundreds of non-professionals took turns creating a work of art online or in person, one stroke per person, or if dozens took turns providing a new chapter or new paragraph to a developing novel? Artists already are experimenting with such art collaborations.

However, the more common interaction between artist(s) and audiences may develop more as Charles Dickens-like scenarios. Dickens famously wrote many of his novels in serialized form, one or two chapters per month, for penny magazines. He often would not write a new chapter until he’d received responses about the previous one, which led him to introduce new elements of plot, character, and description for the next chapter based on reader comments on the most recent. Producers of major movies do this now, using test audiences to first determine what works not just for endings but in other elements of a movie. This has always happened—mid-process input—among some highly-social artists and their friends, especially in the critical reading of short stories, novels, and scripts by writing clubs. With financial and aesthetic incentives so important and with people becoming increasingly more social, could we develop sculpturing clubs, music-writing clubs, and group-painting clubs?

Conclusion

All these new influences--electronic arts, the professionalization of the arts, and interactive art--may

radically affect the future of all the arts. The changes

likely will unfold slowly over decades or even centuries

of time. These new influences may redefine the nature and

meaning of the arts in important ways. At the same time,

increasingly larger numbers of us will have more frequent

access to the fine arts. Hopefully the 21st century will

be a time when the arts can become readily available not

just to people in the richer countries, but also to all

people throughout the world.

---

Exercises

Exercise 1

Write down your favorite kind of TV, computer, or video art. Why is it your favorite? How does it make you feel and think? What would it be like to see it or experience it in person--describe the sensations.

Exercise 2

How do you think your parents or grandparents viewed artists--people who said they were painters, writers, musicians, etc. How do you view them? How do you think they should be viewed in the future?

Exercise 3

Write, in rough-draft form, one or two pages of notes or directions for an interactive stage play, holographic computer program, or written story or video with multiple possible endings that you would enjoy creating. Briefly write an explanation of why you set it up the way you did.

Exercise 4

Write down three or four other types of art discussed in this book that are, in your mind, the most interactive of the art forms. Explain in a sentence or two how or why each may be considered interactive.

Exercise 5

What would you like to see in the future of art in society? What would you like to see in the way of new forms of art or further developments of old forms? Write a half page on each question.

Exercise 6

What are your three most favorite types of art? Imagine that you could create, build, or produce a combination of them? What are some of the steps you would take to combine them? How would the resulting story, view, sound, or other work of art appear? If it helps, imagine you are starting with a specific visual plan, type of music, or plot: you may return to one or more earlier chapters to develop this structure, if it helps.

Exercise 7

If you had excellent skills in drawing a portrait, and you decided to draw a portrait of someone you know well, how would you draw it? What expression would you show on the face? How would you draw the person's body? What would you have the person doing or how would you have them stand, sit, or lie down? What would you show in the background? What kinds of colors would you use in/on the person, and for other objects or background around them? Make a list or description of these elements, imagining them freely. Next, make a second list or description: how does each of these parts of your portrait compare to other paintings or drawings you know about, whether old pictures or new, dark or colorful, with detailed backgrounds or abstract backgrounds?

---

*Image in Chapter Title: Hunchback Leaning on Staff, Sandstone, 10th–12th

cent. CE, Huastec (Mexican), Metropolitan Museum of Art,

www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/310473. Retrieved 25 Mar. 2020.

Most recent revision of text: 21 May 2020

|

---

|

|