|

Experiencing the Humanities

A Web Textbook

|

|

|

Experiencing the Humanities

A Web Textbook

|

|

7-B. Society and Disaster:

How Civilizations Respond

- Long Version -

"The Family Circle" by Pierre Daura, 1954*

Chapter 7-B (Long Version) of

Experiencing the Humanities

by Richard Jewell

Things fall apart; the centre cannot hold;

Mere anarchy is loosed upon the world,

The blood-dimmed tide is loosed, and everywhere

The ceremony of innocence is drowned....

--William Butler Yeats

This is the long version of this chapter (about 7500 words). If you'd like to read a

shorter version (about 4000 words), go to

Short Version.

Introduction--Facts, Feelings, and Future

The above words from famous poet William Butler Yeats describe what many people experience in a disaster. Most people on our earth now can say they have lived in a time of disaster. We all now have in common, as this chapter is being written, the experience of the COVID-19 disaster. Some of you have been part of others disasters. What is your own experience? Just what qualifies as a true "disaster"?

Regarding our worldwide disaster, COVID-19, it is a "pandemic." The word means "a world epidemic (world spread of infectious disease)." Our recent COVID-19 pandemic is the worst worldwide spread of illness in one hundred years. Here is a useful quotation about the COVID-19 pandemic from Arundhati Roy, a winner of the prestigious Man Booker Literary Prize:

Historically, pandemics have forced humans to break with the past and imagine their world anew. This one is no different. It is a portal, a gateway between one world and the next. We can choose to walk through it, dragging the carcasses of our prejudice and hatred, our avarice, our data banks and dead ideas, our dead rivers and smoky skies behind us. Or we can walk through lightly, with little luggage, ready to imagine another world. And ready to fight for it ("The Pandemic is a Portal").

Roy is saying, simply, that a pandemic creates a break in our personal and societal histories--that there will be, for the society and for most of us as individuals, a memory, forever, of a "before" and "after" of this pandemic--and that civilization should make the best of this new world in which it finds itself.

Though she is writing about one kind of disaster--the current pandemic--her words also apply to other types of disaster. In all disasters, life changes for a society, and for a majority of the individuals in it.

How can we best understand disasters? There are typical patterns that we can discover. Using them, we can compare and contrast old disasters with new, and one type of disaster with another. This chapter looks at typical societal patterns that occur in all disasters , and also at patterns that are different for each major type of disaster.

Facts, feelings, and future: One overall pattern for all disasters is the facts, feelings, and future about them. These three elements are the three main sections in this chapter:

Facts--What

are the facts: increased change

(climate change, pandemics, wars, genocides, and shifts in belief)

Feelings--How

do people feel: increased emotional energies

(Kübler-Ross's elements of grief)

Future --

How do people think more: increased awareness/mindfulness

(three main theories from sociology)

Why are these three elements important? If you're interested in why "facts," "feelings," and "future" are especially useful in understanding disaster, the humanities discipline of philosophy offers a simple answer. Philosophy often asks, "What experiences are most basic to life?" In a disaster, three basic experiences in society are: (1) increases in change, (2) increases in human energy, and (3) increases in human awareness/mindfulness. These three increases are what many professional thinkers might label "existential," meaning "of basic human existence."

These three ways in which disaster is existential work as follows:

(1) "Change" occurs because the disaster itself is a significant change from normal societal life: you can measure this change simply by looking carefully at the facts.

(2) "Energy" also increases (often negatively, at first) because of a blossoming of new or strong emotional feelings.

(3) "Awareness or mindfulness" increases, too, as an entire society and its individuals begin to consciously wonder, "What should we do in our future?"

Here in what follows are patterns of "facts," "feelings," and "future" in disasters.

Facts--A Brief History of Change Caused by Disasters

It is very important to get all of the facts right about disasters. In this way, you can better see the patterns from the past. When a major disaster strikes a society, a nation, or an entire civilization, usually--to most people--the experience feels like a blow from an axe cutting the stream of history in two, the "past" from the "new." Most disasters generally are unexpected, as in the current rapidly developing COVID-19 pandemic, which not even most researchers expected to occur with such severity.

At other times, a disaster may be anticipated, even predicted. An example is when the United States and many other nations slowly began seeing the need to defend themselves before World War II actually broke out. However, Even in "planned" disasters such as war, when people know it is coming, the actual birth or beginning of it is like a disaster, whether unrolling or occurring quickly or slowly. For most people, even a planned disaster is a change--similar to having a child or starting a new job--that is not fully anticipated. No matter how much you prepare for it, is still largely is an unknown concerning what it will do to your life. And in any kind of disaster, this change appears most often to society, in its beginning, as a negative experience.

Whether anticipated or not, a disaster is a significant change. People often remember a distinct "before" the disaster and an "after." People may even remember the day, such as when two jets flew into the twin towers of the World Trade Center on 9-11 (2001), or when a country's leader dies. This mark of change occurs, often, for an entire generation or more of people. More important for the purposes of this chapter, the facts of the changes themselves show patterns of development in what happens to societies and civilizations that experience them. This first section summarizes, very briefly, the facts of four major types of disasters in history--what actually happened to societies and civilizations--along with a brief mention of other types of disaster, and a brief discussion of how disasters are more likely to cause "paradigm shifts," which means "major changes in basic beliefs":

Climate change

Pandemic

War

Genocide

Other Disasters

Paradigm (Belief) Shifts

Climate change

First, climate changes are not new to the earth. One of the worst climate changes occurred about 66 million years ago. In the Cretaceous–Paleogene extinction event, about 75% of all life on earth died, including most of the dinosaurs, from an asteroid hitting the earth and causing vast changes in our climate. A smaller climate change, one that had a dramatic historical effect, was a disaster of having no sun, or what we might aptly name the "No-Sun Disaster" of 535-536 CE (AD). It may have been caused by a massive volcanic eruption in Southeast Asia. It reportedly blotted out the sun in a sky filled with dense clouds of dust for eighteen months in many countries. As a result, there was no harvest in many countries for two years, creating mass starvation, the spread of bubonic plague that killed up to one hundred million people over the next two hundred years, and mass movements of whole societies to better territories that caused wars for generations and caused the final fall of the Roman Empire.

This event may have been the single most powerful combination of factors that led to the medieval, middle, or Dark Ages. The Dark Ages, you may remember from history, lasted for hundreds of years in large parts of the world, and for almost one thousand years in Europe.

Pandemic

Second, pandemics also have been a major type of disastrous change. Pandemics are world epidemics of illnesses. They have killed entire species of animals long before humans developed on earth, and many millions of people in recorded history. The bubonic plagues that swept the world, mentioned above, were repeated in the Black Death in Europe in 1347-1666. Also known as the Pestilence or Great Plague, it also was a type of bubonic plague. It killed 30% or more of Europe's population in waves of infection and re-infection for over three hundred years.

An example of a more recent pandemic was the 1918 "Spanish Flu" epidemic, a flu that was unusually lethal. It may have been the second biggest pandemic killer in earth's recorded history, infecting up to 500 million people in the world during a three-year period and killing 15-100 million people throughout the world, or between 1.5% to 5% of those who caught it. The death rate for COVID-19 may be somewhat similar, with current predictions (as of August 2020) suggesting a rate of 0.5% to 4%. In both of these pandemics, actual death-rate counts are difficult to make for two reasons: (a) some countries underreported deaths and (b) the rate of death in first-world countries with excellent health care may be much lower than the rate of death in third-world countries with little or no health care. In addition, in the COVID-19 pandemic, scientists may not know the final death rate for years, as the disease will continue to spread through poor, third-world countries long after the first vaccines are produced and sold in rich countries.

The current

HIV infection or "AIDS" that started in 1981 is another recent example. At first

it began primarily among gay men. But soon it became a more general infectious

disease acquired easily by anyone, male or female, who received transmission of

others' bodily fluids, no matter their gender. The disease has infected at

least 65 million people throughout the world, killing about 25 million of them.

War

War is a third type of disastrous change. There have been many great wars in the history of the world. In the last 2000 years alone, major wars have killed up to 435 million people or more--not counting secondary effects such as famines, genocides, and illnesses following the wars. That 435 million is the equivalent of wiping off the map the entire population of the United States and Canada, or of all the European Union countries. Major wars in or involving China over 2000 years killed up to 200 million, and Eurasian Mongol wars up to another 60 million. The Spanish invasions of the Inca and Aztec Empires and the Yucatan Peninsula alone killed 15-20 million if you add the number of Indians killed in these early incursions smallpox. The disease was new to native populations, and millions had no immunity to it. They were infected by the Spanish soldiers both accidentally and, at times, likely intentionally.

The period of two World Wars in the 1900s killed up to 135 million, the record for one country being 27 million Russians who died in World War II. The World Wars were somewhat different from earlier ones. In wars from early times, there have been large casualties of civilians in addition to soldiers; however, with some exceptions in which mass slayings of civilians occurred--and soldiers throughout time have swept through villages, burning and stealing as they went--the majority of civilian deaths have been secondary, a side effect caused by starvation, prolonged exposure to the elements, and pandemics.

However, the World Wars caused direct and intentional mass deaths of civilians. Just a few examples include mass destructions of entire cities in fire bombings and by atom bombs, mass killings of Jews and many others by gassing and shooting, and the planned mass killing of enemy civilians through starvation. No wars had ever elevated the art of civilian killing to such massive, factory-based, leader-planned killings of so many civilians on purpose.

Genocide

Fourth, genocide is another type of disaster. It is similar to war, except that it is less visible to the dominant culture and can last for dozens or hundreds of years. "Genocide" means the killing of a race or cultural group of people, or the attempt to completely wipe out its cultural heritage. The infamous killing of 6 million Jews in World War II concentration camps is one example. Another is the massacres of Native Americans throughout North and South America. The Americas had an estimated Indian population of over 100 million before European invaders came; afterward, only about 10-20% still lived. They were massacred, given illnesses meant to wipe them out, forced into death marches to inhospitable new areas to live, and their children taken from them to live in forced reeducation programs to "get the Indian out" of them. The effects of genocide continue with racism, disempowerment, poor housing, poor health, and traumatic stress through many generations in families.

African-Americans also experienced a slow-moving genocide, one that used them for financial gain. In the 1500s-1800s, 12 million or more Africans were taken in slavery to the Americas. About 2 million died in shoulder-to-shoulder storage in slave ships. The average lifetime of some field slaves in the Caribbean, nearly all of whom worked in high heat and humidity planting, weeding, and harvesting sugar cane, was as little as five years. The 400,000 African slaves who reached the United States grew, by 1860, to 4.4 million African-Americans, 90% of whom were slaves; by then, they made up 60% of all slaves in North and South America. They, like Native Americans, still experience the effects of genocide in racism, poverty, illness, and limited housing.

Other types of disasters

Other types of disaster also occur, though often they are only regional in the world or a part of a country. History records, for example, that Egypt had a host of disasters such as locusts, flies, lice, and frogs in Biblical times. Such plagues are common throughout history. For example, Africa, Pakistan, and India currently are experiencing, in 2020, a plague of billions of locusts that started the year before. One average swarm of locusts can, in just one day, eat as much food as thirty to forty thousand people, and the swarm can travel as far as 100 miles in that one day. Tens of thousands of farmers are losing most or all of their crops to the finger-length, grasshopper-like insects, causing hundreds of thousands of people to face starvation.

Other types of disasters--breaks in dams, hurricanes, and torrential rainstorms--cause floods in which hundreds or sometimes thousands die. Industrial accidents cause major disasters, too, such as the the release of toxins in Bhopal, India, in 1984 that probably killed 15,000 or more and injured half a million, and the the 1986 Chernobyl nuclear reactor disaster that likely killed 15,000-60,000 people over a period of years and contaminated 1000 square miles of farmland and villages with dangerous levels of radioactivity for decades.

Economic disasters also are common. The Great Depression of 1929-1939 affected the whole world, leaving millions worldwide in greater danger of starvation and of early death. It also likely contributed to starting World War II, the worst the planet has seen. During the Great Depression in the U.S. alone, unemployment averaged 14% for years, peaking at 25% in 1933, and caused a massive change in how the U.S. federal government works when it interceded to help society recover.

Paradigm (belief) shifts

Paradigm shifts also are an important element of disasters. A "paradigm shift" is a change or shift from an old paradigm (old theory, belief, or way of seeing a scientific or societal problem) to a new one. Paradigm shifts in science and society happen historically for a variety of reasons, but they likely occur more often--or more quickly--during disasters. Change is greater, sometimes even sudden, in crises, leading people to need better solutions faster in new ways.

For example, the 1918-1920 Spanish Flu pandemic, against which the world could do little but socially isolate, caused a paradigm shift in science as scientists learned the pandemic was not from bacteria but rather from viruses. The relative helplessness of science at that time may have led to greater study and understanding of viruses and possibly to the faster mass production of better microscopes--ones able to actually see a virus--starting with their invention over a decade later, in 1931.

Another example of a paradigm shift occurred after World War II. Scientists discovered that another world war in which hundreds of nuclear bombs would be deployed would create a "nuclear winter": one or more years with no summers, leading to the death of much or even all humans on earth. In addition, world cultures began to see that allowing countries to go to war without trying to stop them could lead to considerable damage to millions of people, unforgivable suffering, and world economic disturbances. In this new vision of war, the paradigm for dealing with war shifted. The result was the creation of world organizations such as the United Nations and world laws about war such as the Geneva conventions.

Our COVID-19 era also is causing a paradigm shift in how societies search for a vaccine. Formerly, most countries had rules and procedures for how vaccines could be created, tested, and then mass produced, which took two or more years. Now, though, because scientists and societies have seen an emergency in the COVID-19 disaster, most countries are using much faster emergency experiments and testing, and they are preparing much faster to mass produce a new vaccine. Some of these procedures likely will continue long after the COVID-19 disaster has passed. And these changes may also hasten--by years or even decades--scientists' dream of developing a "super-vaccine" that can be adapted at any time to fight any future virus.

Grassroots paradigm shifts

One form of paradigm shift that develops in normal times--but even faster because of disasters--is a bottom-up form of change often a called "grassroots" movement. A grassroots movement consists of a group of people who are less noticed in society, and often ignored by those in power, such as farmers, laborers, the poor, voters seeking to be heard as a group, and others seeking a change.

The name "grassroots" likely was developed in the early 1900s or before because such people were not living in wealthy homes but rather "in the grass" where their movements grew, like grass, from the soil. In the 1800s and early 1900s in the United States, this literally often meant that such movements started on or among farms. The name became extended to any group without power who collectively organize themselves to gain economic or political power as a large group. In fact, it is possible to argue that the American Revolution started as a grassroots movement with the dumping of tea in Boston Harbor and other acts of civil disobedience.

The United States has a long history of the development of grassroots movements. Typical examples of economic cooperatives have included, historically and in the present, farmers' grain and milk cooperatives and workers' labor unions. Contemporary economic and cultural cooperatives have developed in recent decades, too, such as food coops, artists' cooperatives, crafts cooperatives, the Red Cross, and many others. Politically, grassroots movements are second nature to the United States process of democracy and, in particular, voting. Many of them rise and fall around voting periods: these include local get-out-the-vote efforts, often volunteer or self funded; voter information programs; and community organization efforts.

Other grassroots political and cultural organizations may start small and then grow in size to become a regular institution in a community or a nation. In the U.S. the Civil Rights Movement and the Peace Movement, both in the 1960s and beyond, were powerful; the 1980s Peace Movement was even more powerful in Germany. Other U.S., groups often started small, became big, and still exist today: the League of Women Voters, National Organization for Women (NOW), and the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) are just three of many dozens of such movements and groups that started with volunteers organizing themselves.

Examples of highly partisan grassroots movements include the 2016 political campaigns of both Bernie Sanders (Independent/Democratic) and Donald Trump (Republican), especially as their campaigns began. In these campaigns, both politicians came from behind thanks to important volunteer grassroots movements and word-of-mouth news by large numbers of excited voters. Both movements came, in time, to be helped by additional funding from politically powerful and rich professional political organizations. As a result, the two candidates' campaigns were powered by both grassroots organization and professional politics. Sanders didn't find enough voters to win his primary; Donald Trump did, and went on to become President.

Grassroots movements often are a paradigm shift because they seem to come from nowhere and develop, sometimes, into powerful new and even unexpected ways of thinking, feeling, and acting. But why and how are grassroots movements important in a disaster? Often, grassroots movements are born from disasters, or small movements may suddenly grow, dramatically, during or after disasters. Often they create a badly needed change when few people know of the need for such change until the disaster made the need obvious. And their overall effect on democratic nations is to encourage individual self-expression, freedom, and economic improvement.

---

In conclusion,

disasters can happen quickly or slowly; they can last briefly or for many years.

In addition, the longer they last, the more they tend to change a society,

setting it on a different course in history. The type of disaster--and how short

or long it is--also can have profound affects on a society's emotional

energies--as discussed in the next section, below.

Feelings--The Emotional Energies in a Disaster

The emotional energies that a society feels in the short- and middle-term of a disaster can vary dramatically. Feelings may run high for many, and communications media may often highlight and broadcast individuals' emotional energies, from the society's leaders to some of its least noticed citizens. Often the emotions of a disaster are initially negative. For some, they stay negative; however, others work to develop neutral or even positive feelings. As a society first begins to realize it is in a disaster, and then as the disaster proceeds, waves of emotional energy cycle through the population. This chapter talks about "revitalization" after disasters, Dr. Elisabeth Kübler-Ross's "Five Elements of Grief," and Dr. Lise Van Susteren's "Four Emotional Reactors" personality types.

Sudden change and revitalization of society

Famous cultural anthropologist Margaret Mead observed that a society can change in as little as one generation. Disasters often are a cause of a society's quick change, as discussed in "Paradigm (Belief) Shifts" just above.

Another anthropologist, Anthony F. C. Wallace, developed a related and well-known theory of a society's "revitalization"--of positive change. Wallace argued that after a normal period of life and of gradual positive change in a society, a period of stress can occur. As this stress develops, many individuals in a society become increasingly unhappy.

As a result, normal life in such a society is no longer satisfactory or, sometimes, even possible. This means changes are needed, first in individuals and then in the entire society. At that time, society begins to change how it sees parts of itself and its culture. This change in its vision of itself causes changes in how people communicate with each other in the society, and then causes actual changes in the society's life patterns. In a successful society, new changes are instituted--with a "new normal"--and then this society is "revitalized." It can once again live comfortably, or at least knowledgeably, with how life normally works, but with the newer, better patterns now incorporated into the society.

During the stages Wallace describes as a societal change, many strong emotions may dominate. This is true especially in disasters. These strong emotions are part of what a society cannot avoid, and so it must communicate and handle them. The emotions may vary quite a bit.

Kübler-Ross's five elements of grief

However, one famous model developed by Dr. Elisabeth Kübler-Ross, an American-Swiss psychiatrist, well summarizes five dominant emotions in people as they react to a disaster. How a society deals with these five primary emotions can help us better understand people's reactions in a disaster. In addition, Kübler-Ross offers, in the fifth of the five emotions, an emotional goal for individuals and society that is similar to Wallace's final goal of a society successfully revitalizing itself.

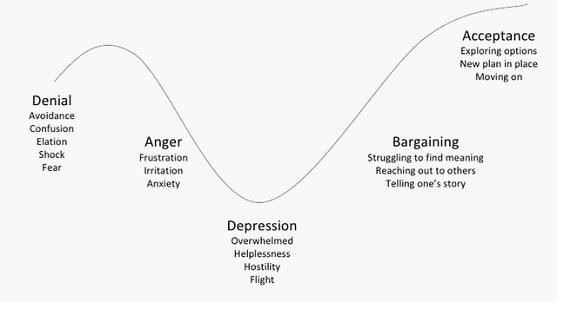

Kübler-Ross's well-known model is charted below. The five emotions show how people handle grief. Originally, this was a psychological model meant to explain how terminally ill individuals and their loved ones often react to the news of their own or others' impending death. However, the Kübler-Ross model also is helpful for understanding how a society and sub-groups within it respond emotionally to a disaster:

Kübler-Ross's Five Elements of Grief

"Kübler-Ross Grief Cycle," U3173699 / Creative Commons License,

28 Aug. 2019.

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Kubler-ross-grief-cycle-1-728.jpg.

Retrieved 17 Apr. 2020.

Please note these three disclaimers about this graph:

Disclaimer 1: Kübler-Ross herself pointed out later in her life that these five elements of grief may occur in a different order, not just as above; and that only some of these elements may occur, rather than all, in any one individual's crisis. The same would be true for applying them to sub-groups of a society. In addition, some people may experience two or three of these elements at the same time, or experience a second or third emotion and then return to an earlier one. The goal for psychological health in Kübler-Ross's system is to reach the end: "Acceptance."

Disclaimer 2: Kübler-Ross meant these five elements to apply only to individuals. This chapter takes the step of applying them to a society in disaster.

Disclaimer 3: Initially, in her early publications of these five elements starting in 1969, Kübler-Ross showed the five elements in this order: denial, anger, bargaining, depression, and acceptance. She later changed the order to what is shown in the graph above.

Denial/shock

In the "Denial/Shock" experience, the chart above notes that "Denial" may bring one or more of the following feelings: "Avoidance, Confusion, Elation, Shock, Fear." It is relatively easy to see how Kübler-Ross's element of "Denial" applies to a society in a disaster. Clearly, in the beginning of a crisis, many people deny it, consciously or unconsciously. They often start with shock or surprise. Then they think, "That's false news," "Nothing like that could seriously happen," "It won't come to our country," or, even more simply, "Let's just ignore it and continue on as normal."

Other people in the denial stage may feel shock or fear as the first news of the crisis sinks in. For example, in the recent COVID-19 pandemic, many people's first reaction was that the virus would remain in China and never, ever enter the U.S. , then that it would not enter beyond the country's coasts, and then to not believe it would have any affect on them. This is a typical societal reaction in most disasters throughout history. Some parts of society will continue their denial; others may hyper-react with panic. Still others might even feel "elation" at the change or challenge.

Anger

For the "Anger" experience, the chart above lists, as part of this element, "Frustration, Irritation, Anxiety." Many people react sooner or later with anger. They may be angry that this threat is happening; angry that they, society, or the world must deal with this threat; or angry towards those who are announcing it or trying to manage it. There especially can be anger toward another society, country, or individuals who might be blamed for causing the disaster. Along with this anger is frustration and irritation at having to deal with the crisis, and anxiety about what will happen. Some subgroups in a society even try to maintain anger to help motivate and empower them.

An obvious example of how anger can dominate a society in some disasters occurs in wars: for example, the beginning of World War II. Each country that was attacked at the beginning of World War II focused its shock and fear by becoming angry at the new enemy attacking it. Newspapers and politicians inflamed this anger to use it as fuel for the will to fight. On the other side, each country that was attacking felt it already was in the middle of a disaster, one caused by the enemies it was attacking: each attacking country spent years building up a great societal anger for economic unfairness and other punishments it believed it had experienced. And it, too, built up this anger through newspapers and politicians to a fever pitch of war effort thinking war was its only means of escaping its disaster.

Such angry actions and reactions are occur often in many disasters. It is inevitable, even natural, for parts of a society to feel some kind of anger in a disaster. Disasters are, by definition, dark, unfair, and unjust. However, scientists and health experts point out that continuing anger in an individual is emotionally and physically unhealthy for the person, and painfully divisive for those around that person. The same is true in a society, and even more so in a disaster when social changes must be made. There is no need for anger to fuel change, as other powerful emotions feed a society's dedication.

In addition, a society needs to be able to think calmly and rationally in order to more quickly adjust to its disaster. If part of a society blocks necessary change, a certain amount of anger might occur against this blocking and be helpful in making better plans. However, even this kind of anger works best--especially in a disaster when people's emotionally sensitivities are higher--when transformed cautiously into fair, honest, socially-positive ways.

Yet another interesting and related factor about anger in disaster is that some individuals and subgroups in a society feel, instead, a sense of joy, pleasure, or purpose. Once they have recovered from the surprise of the change, they see an oncoming crisis as an interesting opportunity. This can occur from their enjoying danger, seeing an economic opportunity, experiencing elevated levels of adrenaline, or simply liking the opportunity to be useful during a challenging time.

Depression/despair

For the emotional experience of "Depression," Kübler-Ross lists the following characteristics: "Overwhelmed, Helplessness, Hostility, Flight." Underneath the surface of a disaster is a less-discussed trend among many of feeling overwhelmed or helpless. This often leads to people losing their emotional energy. Those already inclined this way may get worse. A decrease in exercise or proper nuturients during a disaster also can make lethargic depression worse. There also is a type of "high-energy depression" in which people have physical energy, but this either expresses itself as anxiety and/or a loss of meaning in life.

In general, though, depression and despair are considered a loss of energy. Some people, after (or even before) they have already experienced high-energy panic, confusion, doubt, and/or anger about a disaster, may fall into a lethargic or low-energy depression or despair: weighted down by the crisis and at a loss about what to do. Those most affected by the disaster--having lost their jobs, having been invaded, jailed sickened, crippled, or having someone close to them killed--are more likely than others to experience depression or despair.

Some people take flight--either figuratively in their heads into a world where the crisis doesn't exist, or literally by going to another geographical place. In extreme cases, especially in war, some people may be forced to flee, physically or psychologically. However, if flight is a freely chosen option, a little bit of it sometimes can be healthy: places, times, or conversations each day in which, for a little while, you can get away from being aware of the disaster, or occasionally a geographical move.

Those who suffer severe losses in war or another type of disaster often find they cannot avoid the ongoing and sometimes all-consuming element of "Depression/despair." In the type of disaster known as genocide, in particular, the crushing of a society's culture and opportunities can cause ongoing depression and despair among millions who have lost hope, affecting their psychological, emotional, and physical health--and their lifespans--negatively. For people experiencing the extremes of war and ongoing genocide, especially, their ability to reach Kübler-Ross's goal of emotional "Acceptance" is very difficult.

Bargaining

For the emotional experience of "Bargaining," Kubler-Ross lists "Struggling to find meaning, Reaching out to others, Telling One's Story." For many, a period of bargaining begins at some point. Kübler-Ross means this term, "bargaining," to refer to bargaining against the idea of having to fully deal with the fact of an oncoming death. In a society in crisis, "bargaining" includes trying such options as making a deal with spiritual powers to be a better person or pray more, deciding to become more ethical in order to lessen the effect of the disaster, and developing the story of your own or your society's life to either show why the disaster should not be happening or to block out its importance. All of these in "Bargaining" are ways of putting off full logical, factual acceptance of what the disaster is and what it means.

However, the problem with such negative, fantasy-driven, or memory-lane bargaining is that, in a society that expects to heal from the disaster, it slows down the healing process. If a large number of people begin ignoring the need for responding to a disaster intelligently and promptly while others work hard use fantasy bargaining, then the society itself may be in danger. Most successful societies throughout history have had a basic cultural understanding that "alone we die but together we survive." Thus false bargaining using fantasy is useless and destructive.

On the other hand, once all the facts are known and a society has had an opportunity to discuss matters reasonably within itself, then bargaining among subgroups may be healthy. In some bargaining, a society may choose to allow one subgroup to try one solution, and another subgroup try another solution, then examine the results. This is, in a way, what happens when pandemics sweep the world--as COVID-19 has, now--with one country responding with one set of guidelines, and another country trying a different set of guidelines.

This kind of social bargaining really has more to do with Kübler-Ross's final "Acceptance" stage in which a society looks at all the facts and works to best develop a rational response. If this healthy, fact-based form of bargaining is used, it must be within a context of freedom, not forced on one social subgroup. An example of such societal bargaining that is healthy is that in war, some people are allowed to stay home and not become soldiers if their civilian work is unique and necessary, or if one adult in a family is the only available parent for the children.

Acceptance

In Kübler-Ross's list, above, for the element of "Acceptance" includes "Exploring options, New plan in place, Moving on." Acceptance does not mean giving in and giving up. Rather, when applied to a disaster, it means, first, that you actually are willing to accept that a societal crisis is happening and that facts must guide what happens. Second, functional societies believe that if you have a skill that might help--and if you are economically, physically, and emotionally able to use it--then you should.

What does an "Acceptance"-heavy culture look like? There are many societies that survive and even thrive after disasters, even if recovery may take months, years, or decades. Cultures that do best work to recognize what is happening in a disaster, and to inform each other through good communication. A functional, "acceptance"-heavy culture especially values three traits: (1) accurate science, (2) factual news gathering, and (3) fair and balanced politics. The first of these three means, ideally, that the scientists in the society use fact, perform research, and help the populace understand what they are doing. Second, the ideal news gatherers help communicate the facts accurately to citizens. Third, the ideal politicians work to learn the needs and wants of everyone and then organize what must be done in an open manner.

Along with these three traits is, in a functional society, the question of how people in power--with money or influence--also will work for the good of the entire society. Do enough people put aside their own self-interests or even sometimes sacrifice their self-interests, in order to produce better conditions for the society? This, too, is a necessary element of "accepting" a disaster and revitalizing a society.

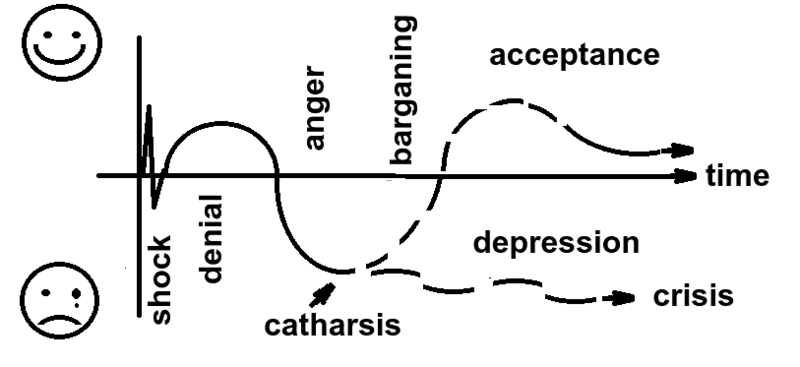

Can a society fail?

In fact, here is a more recent chart reflecting how some individuals, a sizeable sub-group in a society, or occasionally an entire society might not reach the final positive "Acceptance" element. These individuals, a sub-group, or the entire society may become stuck, instead, in the "Depression/Despair" element. It is important to remember that Kübler-Ross herself, later in her career, stated that not all people experience all five elements, and not necessarily in the same order.

Positive and Negative Outcomes in Kübler-Ross' Elements

“Diagram showing two possible outcomes of grief,”

Timpo.

Creative

Commons License,

19 Nov. 2017.

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:K%C3%BCbler_Ross%27s_stages_of_grief.png.

Retrieved 1 June 2017.

And if, as Kübler-Ross says, individuals might experience only some of these emotions in a disaster, what if they never even reach "Bargaining" or "Depression"? This would mean they are still stuck in "Denial/Shock" or "Anger."

If so, these unfortunate individuals are still not admitting that change has happened, or they are refusing to understand they, themselves, must change. Such denial of even the basic fact that a change has happened leaves the individuals--or an entire sub-group of society--with a psychological problem: if you can't admit the facts before you, then you cannot survive well in reality. If a large enough part of society remains in denial or anger, this in itself can doom the society to insufficient change in the midst of a major disaster.

Kübler-Ross would say such people's individual psychological health is imperiled, scientists would argue they they may be unable to accept important paradigm shifts, and one group of social scientists in the next section below--the functionalists--would suggest that the entire society might be unable to return to proper functional living. In worst-case scenarios, such a society either might not survive the disaster, or the disaster might mark the gradual fall of the society and its replacement by another.

An alternate: Van Susteren and Colino's "Four Emotional Reactors" personality types

A recent alternative to Kübler-Ross's "Five Elements/Stages of Grief" is psychiatrist Lise Van Susteren and Stacey Colino's "Four Emotional Reactors" personality types. Each type describes the primary way in which a person may react emotionally in negative situations:

"The nervous reactor: You are anxious, worried, fearful, or apprehensive.... You can't escape a feeling of unease.... [I]t's an adaptive instinct that can help you stay attuned to threats and uncertainty and take action.... The drawback is that you might have trouble turning off your worries. To restore your emotional equilibrium: [Take] time every to day to relax your body and mind.... [P]ut yourself on a 'media diet' by limiting how often you'll engage with the news and social media. Also, reduce your intake of stimulants...."

"The revved-up reactor: You are frenetic, agitated, hyper-reactive.... when an issue or worry ratchets you up, you want to swing into action,...doing more or acting faster.... [T]his...might seem proactive, [b]ut it might also be an unconscious attempt to distract yourself from...deeper, more painful emotions. In the mental health field, this...is referred to as 'negative urgency....' To restore your emotional equilibrium: Slow down and prioritize your actions.... [Exercise] your critical thinking skills.... Schedule downtown,...[especially] enjoyable leisure activities.

"The molten reactor: Your emotion...is marked by irritation, indignation, maybe even anger and hostility. You might feel besieged, frustrated, or aggravated, [making] you feel inclined to push back or lash out [and feel] your...dissatisfaction needs to be expressed to make other[s] more...responsible for their actions. To restore your emotional equilibrium: Think about fixing, not fighting. [M]anage your angry feelings--by monitoring and reframing them in a more constructive way, engaging with others...and using relaxation techniques.... [R]esearch has found that narrating a story about a situation or event that upset you, using the past tense, reduces emotional distress....

"The retreating reactor: You respond to emotional triggers by withdrawing,...turning inward or using alcohol, food, or other substances to numb your mood. [Y]ou might have a sense of powerlessness, despair or resignation, believing...what you do won't make a difference.... [T]his...is a form of self-preservation.... But it can backfire, [leaving] you stuck in negative emotions [and] depression. To restore your emotional equilibrium: Remind yourself that your personal choices [are] influencing people around you.... [R]emember that getting or giving a hug...can stimulate the release of the bonding and calming hormone oxytocin. Also, practic[e] gratitude...."

--Source: See "Recommended Readings and Bibliography" at the bottom of this page.

Van Susteren and

Colino point out that research shows all four reactor types "can benefit

emotionally from helping others." The negative situations. The negative situations

causing these reactions can be personal, within a group or community, or in a

larger society. When disaster occurs, these four types of negative reactions are

common.

---

In conclusion,

Wallace's "revitalization" theory, Kübler-Ross's "Five Elements/Stages of Grief,"

and Van Susteren and Colino's "Five Emotional Reactors" can help you better understand what happens with the emotional energies experienced by a

society in disaster. Other theories also may be helpful, especially as

we look at the future of a society as reshaped by a disaster--which is the

subject of the next

section, below.

Future--More Awareness/Mindfulness

Finally, in a disaster's future--in the middle and long term--a society becomes more aware or mindful of itself and of its current societal patterns. This increased thoughtfulness--or deeper awareness of oneself and others--leads people to reexamine what they should do as individuals and as a society. Great Britain's World War II leader and Prime Minister, Sir Winston Churchill, said, "A pessimist sees the difficulty in every opportunity; an optimist sees the opportunity in every difficulty.” How, in fact, does a society use its awareness or mindfulness to become better--or sometimes worse--because of a major disaster?

Three main theories can help us understand the patterns of how such mindfulness might occur. These three theories are primary ones in the discipline of sociology: the humanities discipline that tracks how people behave in groups, societies, and civilizations. As you read this section, you may want to ask yourself which of these three main sociology theories best fits your own experiences:

Symbolic interaction theory:

for the purposes of this chapter, how society communicates in a crisis

Conflict theory:

for the purposes of this chapter, how society handles conflict in a crisis

(and how different cultural or class groups may conflict with each other in a

crisis)

Functionalist theory:

for the purposes of this chapter, how a society adapts to a crisis

Symbolic interaction theory

Macro ("big-picture") symbolic interaction theory tells you how a society shares important information through different types of "languages"--like radio and talk (oral language), TV (oral and visual languages), and the arts (artistic languages). Symbols are important. Symbolic interaction theory suggests that in a crisis, the symbols of communication about the crisis are especially important, as is how people interpret those symbols.

If, for example, the main symbols used to convey a war are videos and pictures of people dying--as often was the case during the Vietnam War--what is conveyed is death and reactions to it such as panic and fear. However, if the main symbols are highly patriotic, as they were in World War II--with posters of "Uncle Sam," "Rosy the Riveter," and tanks overcoming the Nazis--then what is conveyed is patriotism and power. In any disaster, while the message itself may be about the crisis, the symbols used to convey it create very different types of feelings and thoughts in society.

In a pandemic, if a country is powerful enough to fight it, many of the symbols that a practical society uses will emphasize pictures and discussion of what is needed to combat the disaster. In a society like this, you may see many news programs, online pictures and links, and news articles about the medical devices needed (masks, respirators, drugs, and medical personnel). Often, statistics are shown daily, which can have both a positive and negative symbolic affect on people's thoughts and emotions.

In the 1918-1920 flu pandemic, for example, much of the media simply ignored the flu or did not feature it heavily, so people not only didn't know much about it but had less information with which to combat it or worry about it. In the 1952-1954 polio epidemics, however, pictures and news articles were often distributed showing young children fighting for their lives in large "iron lungs" that were like giant iron barrels surrounding all but their heads, and of terribly polio-crippled people stricken in the height of their youthful careers.

Symbolic interaction theory also would point out, regarding a crisis, that some symbols have different meanings to people, thus causing different interpretations in society. For example, a picture of elderly people bedridden from a deadly virus might in some groups cause sorrow and empathy for the old; in another group, the picture might cause righteous indignation that the elderly are suffering more than others; and in still another group, the picture might cause a feeling of relief because the viewers are much younger and think that only elderly people can get sick. Because people interpret pictures differently, they can use a symbol (a picture, story, or words) in different ways, too, as they talk about a crisis.

How symbols are interpreted in a crisis, and how well different sub-groups of society discuss these symbols, is very important. Both interpretation and discussion are needed for a society to reach Kübler-Ross's emotional "acceptance" stage during the disaster, and to create Wallace's "revitalization" goal after the crisis is finished.

Conflict theory

Conflict theory looks at several aspects of conflict in a crisis. One is how the society as a whole suddenly must deal with an often dramatic change, whether war, a pandemic, or other crises; how that conflict causes trouble in society; and what, if anything, the society can do to relieve the conflict.

On a basic, existential level, any disaster is by definition a cause of conflict: humans are fighting something that is not their normally desired way of life. Conflict theory looks at how different groups deal with this new conflict. Some groups, for example, are hit the hardest by the crisis, such as the poor; those who by racial, religious, or cultural makeup are not in power in their country; women in general; often, children and/or the elderly; and other poorly represented groups. Conflict theory also points out to which groups might even be blamed and suffer as a result of that blame, such as the Japanese and Italians forced into internment camps during World War II; or Asians experiencing racism in the United States during the COVID-19 pandemic because they are blamed for the start of the pandemic in China.

Conflict theory also looks at both the conscious activities and motivations of people in a disaster, and the unconscious or automated activities and motivations--those that people continue to use without giving them sufficient thought. During a disaster, some conscious and unconscious activities and reactions come to the fore, activities and reactions that always were there in society but quiet or seemingly hidden: a disaster makes them more evident. Thus a disaster can be a barometer, a measuring, of how different classes and cultural groups really feel about each other, about differing cultures and classes, about gender differences, and about money, wealth, power, and the lack of these.

What does conflict theory ultimately mean in a disaster? Its important lies in how a society handles it. If societal conflicts help the society more fully reach the goal of Kübler-Ross's "acceptance" during the disaster, and Wallace's "revitalization" after the disaster, then that conflict may have been productive for that society.

Functionalist theory

Macro or big-picture functionalist theory explains how people interact in different parts of society to share and make improvements. The general assumption is that a society usually is self-sustaining. That means, especially in a crisis, the assumption is that a society has its own best interests at heart and, in general, will try to make the best of a crisis. Some functionalists also may examine why and how such positive self-improvement can break down, and what the practical solutions are to solving that problem.

On the positive side in a crisis, according to functionalist theory, if a society is prepared, it can then act with efficiency. For example, if war is approaching, a functional society will start a draft of eligible soldiers: the United States, for example, requires all young males to be registered for military service. Other countries actually require one or more years of active training and/or military service: just a few of many examples are Mexico, Norway and Sweden, China, and Russia. Many countries develop vast stocks of supplies such as war weapons, medical supplies, and storable food that they might need for one or more years in advance. For pandemics, some countries build up medical supplies and equipment. For climate change, some governments large or small will use scientific data to determine how to plan housing, flood protection, and other details for years in advance.

The negative side in functionalism is what is either unconsciously forgotten or missed, or is purposely pushed away from conscious awareness because society does not want to deal with it. Functional failures may include poor small- or large-government planning for and preparation or distribution of physical resources at several levels. Second, it may include poor preparation by a society in general for handling a crisis. Third, there may be poor encouragement, during a crisis, of individuals to meet the crisis with their own contributions when possible, instead of depending on others to handle the problems.

Functionalism has one great advantage, however, in a disaster. Disasters are factual events, and functionalism as a theory is meant to create better functioning in real events. Using a functionalist perspective thus can help further motivate symbolic interactionists and conflict theorists to actually do something--to try to use their intelligent observations to help a society reach Kübler-Ross's emotional goal of "acceptance" and Wallace's ultimate goal of "revitalization."

All three of these theories--as well as others not included here--help us understand how conscious awareness--mindfulness--operates to deal with a disaster. On the positive side, the rational assumption is that a society functions and acts best when it is consciously aware of itself as a society, and that by increasing its own awareness or societal mindfulness, it can make appropriate changes for a better future. Sociology also recognizes, however, that not all societies are willing to make necessary changes; as a result, says sociology, it is possible to chart--to predict--how some societies may fail.

Conclusion: What Can Be Done?

If crisis happens in your society--or in your civilization--what can you do? Experts in both crisis management and psychology say that we should do everything we can to deal with our negative responses, learn or use rational positive responses, and work for a better future. We can join groups who do this or work on our own. Additional advice is to replace what we have lost with similar activities: for example, in the COVID-19 world pandemic, a large number of people began using online social-meeting software programs to see each other and talk together on their screens. We may not be able to avoid the physical changes that cause societal changes.

However, we can take the increased energy from such changes, whether positive or negative, and turn the energy into useful, practical, and positive outlets and activities. As our own conscious awareness, our mindfulness, also increases during a disaster or other crisis, we can go with the flow: be aware that we have become more mindful, take advantage of that new mindfulness, and use it to think and feel in more positive ways, rather than give in to negative thinking.

Crises and disasters can be mild to major, and they can differ dramatically in their affects on different individuals, groups, societies, and civilizations. However, with whatever we are faced, we can choose as human beings to make the best of it, to use the disciplines of the humanities, the sciences, and all of our practical, common sense to learn as much as we can in order to make good decisions. There is nothing more that we can do. And nothing less.

Exercises

1. Imagining the bad: that something bad happens to your group of friends, your community, or your town, city, or state. Make a rough outline or description of what this event is: What would it look like? How would people react? How would it affect you personally? After writing your rough outline or description that answers these questions, make another rough outline or description answering the question "How might you personally respond negatively to the event, and how might you also (or instead) respond positively?"

2. Describe the worst event or result of the COVID-19 pandemic for you. Then describe the best event or result that happened in, during, or because of it.

3. How did you think of war--its causes, meanings, and/or purposes--before reading this chapter? Has this chapter changed your mind about any of that? If so, what and why? If not, why not?

4. Answer these questions on paper or in a group. Did you know all of the past history of genocide against Native Americans or African Americans? What was new to you? What have you known for a number of years? How do you feel about what has happened to Native Americans or African Americans in their worst years--centuries ago--when people were trying to exterminate them (Indians) or enslave them (Blacks)? How do you feel about either or both groups of people now? What do you think they should do? What do you think you can do to make things better for them or others?

5. Regarding the subjects in "4" above, create a quick, rough-draft list of ten to fifteen questions that might create a good debate in your class--questions that could reasonably be debated as either "pro" or "con," or perhaps simple factual questions worthy of more research. Then revise your list of questions by combining some and deleting less important ones so that you are left with a list of five to seven good debate questions. Then you or your classmates could choose some of the questions to either debate or to research.

6. If you had to go through a drastic, immediate climate change such as from a super-volcano or a large asteroid creating two years of no sun, what would you do? Your family? Where would you go? How would you best survive?

7. How does

thinking, reading, and/or talking about disasters like in this chapter make you

feel? Why? Does that lead to any change in the way you think, feel, or act? Is

that change good or bad? Why or why not?

Recommended Readings and Bibliography

For general books, films, and art to view of disasters: see Chapter "7-D: Films and Readings on Disasters."

Sources and readings for just this chapter:

Camus, Albert. The Plague. A short novel published in 1947 by the famous existentialist author about how the plague strikes a French town, and how people respond, eventually conquering their fears. This novel is a short and very accessible book-length introduction to Camus' French existential philosophy, as well as an excellent picture of what a plague is like. The full-text version is available free at https://archive.org/stream/plague02camu/plague02camu_djvu.txt.

Dafoe, Daniel. A Journal of the Plague Year. A short novel first published in 1772 about a young man's experiences in the 1665 Great Plague of London. Though somewhat fictionalized, Dafoe makes a great--and successful--effort in giving exact details and statistics of what happened in London during that bubonic plague. Full-text book available free at www.gutenberg.org/files/376/376-h/376-h.htm.

Diamond, Jared. He advocates looking at history through multiple disciplinary

(scholarly) lenses. Two of his popular science books are especially worth

looking at in terms of disasters and how they affect societies:

(1) Guns, Germs, and Steel: The Fates of Human Societies (1997; won

journalism's Pulitzer Prize). It is Diamond's most popular book. It

is a scientific, sociological, and historical consideration of why and how

Eurasians conquered other people, not because of natural genetic advantages but

rather because of where they lived. Part I examines how plants and animals made

a significant difference in the development of Eurasians. Part II examines how

this led to growth of populations, culture, and epidemic diseases. Part III

examines differences in food and societies in different parts of the world.

(2) Collapse: How Societies Choose to Fail or Succeed (2005). Diamond

examines how societies thrive or fall apart over time, using nine main societies

(including Montana in the U.S.) as examples. The National Geographic Society

100-minute film of Collapse is available free at

www.rottentomatoes.com/m/collapse_based_on_the_book_by_jared_diamond.

"A Giant Volcano Could End Life on Earth as We Know It." New York Times, 21 Aug. 2019, www.nytimes.com/2019/08/21/opinion/supervolcano-yellowstone.html. The earth has twenty "super-volcanoes." An explosion of one of them, however rare, could create results similar to the 535-536 CE (AD) "No-Sun Disaster" for better or worse.

Keys, David. Catastrophe: An Investigation into the Origins of Modern Civilization. This book, published in 2000, suggests how the Middle Ages--also known as the Dark Ages--started, all from one big climate-age event. Thoroughly and exhaustively researched, it still is exciting reading if you enjoy nonfiction. The research still holds up fairly well as of 2020.

Kübler-Ross, Elisabeth, and David Kessler, On Grief and Grieving. Elisabeth Kübler-Ross and David Kessler first published their groundbreaking book, On Death and Dying, in 1969, establishing what they called the "Cycle of Grief." Before her death in 2004, Kübler-Ross and Kessler finished an update, On Grief and Grieving, with new materials added about the meaning of grief and how to handle it. It was first published in 2005 with a more recent edition available.

Kuhn, Thomas, The Structure of Scientific Revolutions, fourth ed., 2012. This book about history and science by philosopher Kuhn was groundbreaking in both fields when the first edition was published in 1962. In this book, Kuhn explains how science moves forward with some steadiness in regular times but may spurt forward, even in entirely new directions, at others, and how this change is not just a speeding up, but an introduction of new ideas.

Sociology Theory: The Cliff Notes version of "Three Theories" is at www.cliffsnotes.com/study-guides/sociology/the-sociological-perspective/three-major-perspectives-in-sociology. A short, more academic introduction by Lumen Learning is at https://courses.lumenlearning.com/sociology/chapter/theoretical-perspectives/. The long version of Cliff Notes' book on sociology is at www.cliffsnotes.com/study-guides/sociology.

Van Susteren, Lise, and Stacey Colino:

(1) Quotations above are from "Tips for staying calm in turbulent times,"

"Wellness" column. "Lifestyle" Section,

www.washingtonpost.com, 2 June 2020. Retrieved 10 June 2020.

(2) This information also can be found in the authors' book, Emotional

Inflammation: Discover Your Triggers and Reclaim Your Equilibrium during Anxious

Times. 20 April 2020, print and online.

Https://www.google.com/books/edition/Emotional_Inflammation/Ma-aDwAAQBAJ?hl=en&gbpv=1&dq=lise+van+susteren&pg=PT1&printsec=frontcover.

Retrieved 10 June 2020.

Wallace, Anthony F.C., "Revitalization Movements." American Anthropologist 58: 1956. https://anthrosource.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/pdf/10.1525/aa.1956.58.2.02a00040. Retrieved 14 May 2020.

---

*Image in Chapter Title:

"The Family Circle," Pierre Daura, c. 1954.

Oil on cardboard.

Copyright Martha Daura / Estate of Pierre Daura, non-commercial

use permitted.

https://collections.artsmia.org/art/61193/the-family-circle-pierre-daura.

Retrieved 4 April 2020.

Most recent revision of text: 19 Oct. 2020

|

---

|

|